There are a lot of misconceptions about the arts, and more specifically the careers of professional artists, in Ireland. Public perception tends to be dominated by the tiny percentage of the most visible artists, and people’s assumptions based on the public image that artists have to portray. This article runs over some of the same ground that I’ve covered in other pieces, which I’ll link to, but I wanted to bring all the most relevant points together in one place.

The creative industries make a major contribution to the economy; about €5 billion in Ireland (it’s hard to find an accurate figure) and as much as £124 billion in the UK’s much bigger economy. And there’s no question that the arts are greatly valued in Ireland, both for this reason, but also for their intrinsic worth to our day-to-day lives. There is a constant demand for art in every area of society, though many people may not be aware of how it is suffused throughout their immediate environment. And yet there’s a big difference between how the arts are treated as a whole, and how artists are treated as workers.

Because as far as worker’s rights go, artists have almost none.

There are almost no full-time employment opportunities for most professional artists in Ireland, so we’re pretty much all self-employed or on contract work. If you’re self-employed in some other profession, you will already recognize some of the challenges. The financial world is set up for people who work regular hours, earn regular pay and have predictable career paths. Everything from paying bills by direct debit to getting an overdraft, renting a flat to buying a house is harder when you work for yourself and can’t count on regular wages. Working for yourself often demands more decision-making every day; you may or may not be able to delegate to others, but it requires a lot of self-discipline and that extra uncertainty of never being able to count on a future income takes an intellectual and emotional toll.

Employment benefits like health insurance, a pension and sick pay insurance are available if you can afford them on your own, but again, these are based on systems of regular payments, nobody’s looking after that for you, and when money gets tight, these are the kinds of things you cut in favour of more immediate bills. When you go on holiday, you’re paying twice, once for the holiday and once for the money you’re not earning. You often have to jump through the admin hoops of others to get paid, and may have to chase payments, even for small amounts, which can be financially and emotionally draining. If you can’t work for any prolonged period because of illness, you’re pretty screwed; not only are you losing earnings, but you might also be losing clients you won’t get back.

Like any other small business, most of an artist’s income is going straight back into the local economy, and artists are often involved in local projects as part of their practice, though you could be working for clients in other countries too – every creative career has a different profile. For most however, it’s a small-scale role that’s recognizable to any freelancer, where everything depends on your personal time and effort, and where people want you to be available when they need you, but don’t need to worry much about how you’re staying afloat.

So . . . that’s normal self-employment.

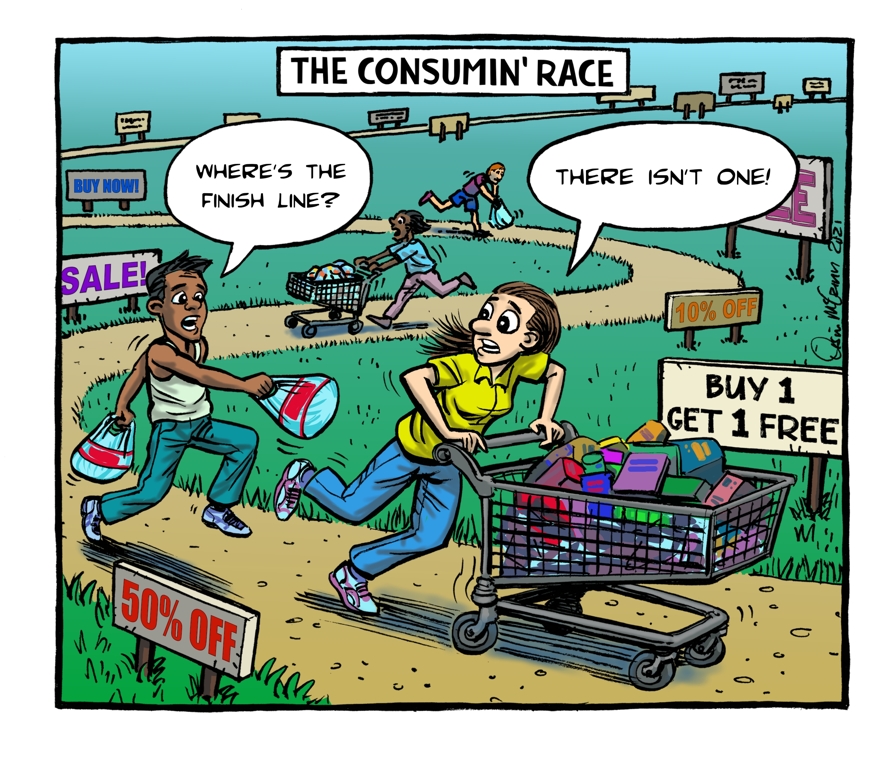

Now imagine you work in an area where there it’s almost impossible to establish a consistent value for your work, people think you’re doing this as your hobby, it’s not uncommon to be asked to work for free or for ‘exposure’, projects may have to be priced based on your original ideas as well as your time, and for many of us, if you have a successful idea, you can never do that exact thing again, because it is the nature of your work that you must constantly be doing something different.

The experience can be like starting a new business . . . all the time. There are so many different kinds of challenges, but this post is about how artists get paid.

First, let’s acknowledge the supports that are on offer, because Ireland does treat its artists better than many other countries, but then it has to, because it’s a tiny market and it has two, much, much bigger English-speaking markets on either side of it. And there has been a long tradition of losing skilled workers to both the US and the UK, because of the lack of opportunities here, so the state has taken some substantial steps to try and hold on to its professional artists. The Arts Council offers generous bursaries to the different disciplines, and this is replicated in a smaller scale through local authority arts offices. Even the Jobseeker’s Allowance has a separate category for artists, recognizing the unique conditions under which we work. And crucially, there is the Artists’ Tax Exemption, which means you don’t have to pay income tax on your creative work once you’ve qualified – though you still have to pay it on any other work you do. That alone has been the reason that many artists have stayed in the country, and after I’d moved to London for a few years, was a definite factor in my decision to return.

The exemption may well be unique to Ireland, I haven’t heard of a similar one anywhere else, but it’s important to realize why it exists. You have to earn that money before it can be taxed, and the government has crunched the numbers. It is a really stark demonstration of the fact that the financial value of the arts to the economy far exceeds the income artists make from producing it, and the tax we would pay as a result.

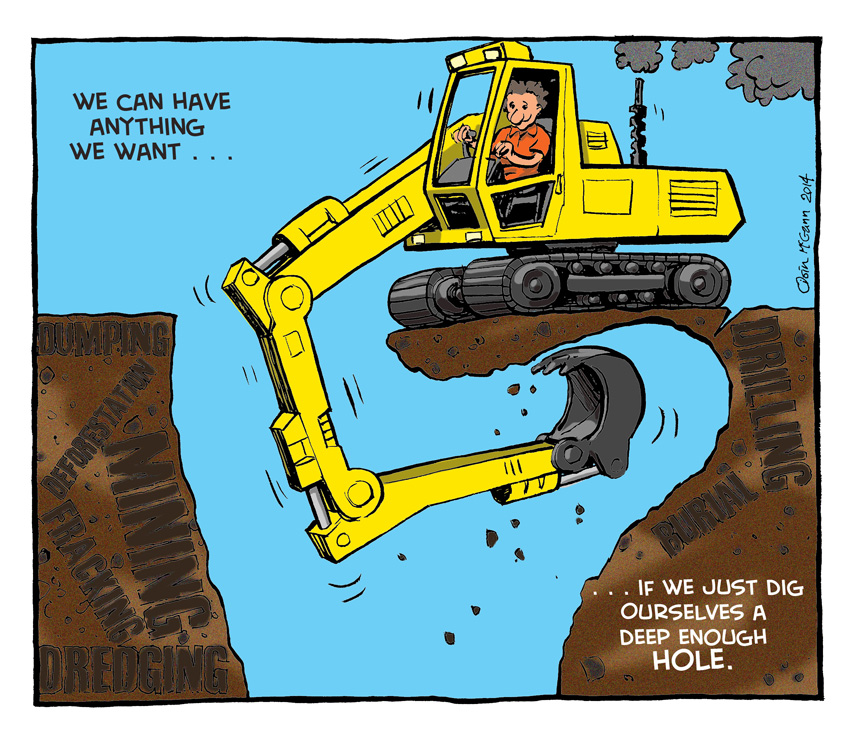

The work of professional artists has more value to the country than we do as taxpayers, so the government-funded supports are not there to ensure the financial security of us as workers, they are to try and ensure an ongoing supply of quality art.

It’s a bit like playing for the GAA. There’s money to be made out of the sport, but generally not by the players. Imagine a sport where you have to play to a professional standard, but still work a full-time job, except you’re doing it on your own. Also, because we have the US and the UK either side of us, you’re competing against the biggest full-time, well-paid professional players from those and other countries, and because they offer greater commercial potential, the work environment operates in their favour. Picture the situation where, like bookshops, cinemas, music venues, broadcasting etc, the sports grounds in your country give those foreign sportspeople more room, time to train and other competitive advantages.

So things like the tax exemption, the bursaries and other supports seem like they must be a big help, but because they fail to address the fundamental problem, the way artists are paid, they’re not helping change that system, they’re actually propping it up. Ireland has seen a big increase in financial support for the arts over the last few years, but the only secure employment is in managing those resources, not in making art.

Like the income provided by the arts industries themselves, these supports are in effect, random rewards, rather than offering any financial security. Up to a point, the more expertise and experience you have, the better your odds, but there’s no form of income you can rely on, year after year. Ireland’s professional artists are basically working for raffle tickets.

When it comes to grants, artists have to fill out forms for every payment they get, which means more admin work, while the odds of getting paid are against you. This act of applying for things and writing proposals stretches across the work environment. Many of us spend significant amounts of time – unpaid time – pitching for projects that might pay very little. I was recently asked to write up a description of how I’d adapt some my children’s illustration workshops to fit in with the theme of a local festival – workshops that were worth a few hundred quid to me – only to be told after I’d provided it that they had decided not to run these kinds of events this year. It hadn’t taken me much time, but this kind of thing happens a lot. There is an expectation that you will provide work and ideas for a job up front, and you can be seen as difficult if you object.

There are tens of thousands of of full-time jobs in the creative industries, but almost all of them are to do with managing, promoting or distributing the work of artists. The artists themselves cannot expect that kind of job security. As I’ve said, the vast majority of artists are self-employed or do contract work, which means that, although there are entire industries based on the work we do, they never have to take any responsibility for the livelihoods of the people they are entirely reliant upon. This is not necessarily the fault of any company or organization within that system – they are often run on shoestring budgets themselves – but it wouldn’t hurt for them to question it more often.

It would be more accurate then, to think of artists, not as workers, but as a natural resource to be mined by others. And you do not pay the ground for its gold. Let’s take publishing as an example:

I want you to think about how a book ends up on your shelf, or on your e-reader. For the sake of simplicity, I’m going to keep the numbers really basic and very conservative: Let’s say a publisher gets a thousand novel submissions a year, but can afford to publish ten new authors. And let’s say that just one of those books is a moderate hit. Nobody will be able to tell you with any certainty which one of those books it will be. For that one hit, there were a thousand books written.

If we’re kind and we say that a novel takes six months of solid work to write, then that’s six thousand months of work done. The publisher has paid for sixty months of that. But despite the advances that make headlines, in most cases, they almost certainly haven’t paid a living wage for that work. Actually, it’s probably only a fraction of that. This is reflective of the size of the market here; you could make the bestseller lists in Ireland every year and never make minimum wage from the royalties.

There are no villains here. Publishing is a risky business, and for most of the people who are employed in it, it’s not very well paid, but by far the biggest proportion of the risk on any book is taken, not by the publishers, but by the writers. The publisher can choose from six thousand months’ worth of work, knowing they only have to pay an advance for the books they want, and that advance will almost certainly not reflect the amount of work that’s gone into each book. The rest of the financial risk lies in the time and effort invested by the artists. Most of us understand this going in. Unless you have a contract for a book, you’re doing work on spec. Depending on where you are in your career, your prospects of ever getting paid for that work can vary wildly.

On top of all that, for most books, the writer is the main form of marketing and advertising. We’re expected to go out and do events to help sell the book. And the demand that we spend more and more time online, contributing work for nothing is a common feature of the job. And if the book doesn’t sell, there’ll be an implication that it’s because the author didn’t do enough. This is implicit in the increasing move towards celebrity books. Authors seem to be expected to provide publishers with ready-made audiences.

It is only because of your love of the process that you allow yourself to be drawn along by the hope of getting that winning ticket, of achieving enough of those successes to make it worth all that time and effort.

But you take the risks and do most of the work, so you get the rewards, right? You get the biggest cut? Right? No. Typically in traditional publishing, the author gets the smallest cut after everyone has taken theirs: the retailer, distributor and publisher. Again, there’s no excessive greed here – that’s just the system.

There is a tiny fraction of artists who are successful enough to make them independently wealthy. There are some more, like me, who manage to make a living, but that’s increasingly difficult to maintain over a long timeline. For all the rest, they can only dream of reaching that stage. Many writers make their living at something else, providing the publishing industry with a steady supply of free work. Work it can choose to use or discard as it wishes.

Imagine working two jobs, the first one being used to support your ‘employer’ in the second one. Most artistic disciplines have their own version of this situation, but the essential elements are common to all of them.

Unlike everyone who’s employed in the creative industries, as a self-employed artist, you can’t look forward to some kind of support at the end of your life, if you put in enough time and work, beyond the same state pension that everyone gets.

Every challenge you face, every hit you take, you deal with on your own. It is a system of attrition. It means that the more committed an artist is to their career, the greater the risk they take with their financial security. It’s how the arts industries can keep rolling along year after year. Because they’re on a road built on thousands of collective years of free labour, leaving used-up artists in their wake – artists who have insulated them from the greatest risks involved in their business.

Most professional artists can tell you of the costs that build up over time; the stress of constantly dealing with uncertainty, running up against bills you can’t pay, the inability to get credit to invest in your business or help get over low points, the social stigma that comes with these things, your decisions to take a break or go on holiday or buy a house or start a family, putting off dealing with health problems and the consequences of that over the long term and the constant pressure to quit and spend your time doing something that will pay a decent wage.

Being able to stay afloat in this unforgiving environment is demanding for anyone, but these challenges make it all the more difficult to break into a career in art if you come from a disadvantaged background, if you’re disabled or a single parent or if you face any number of other additional obstacles. This in turn means that those who are underrepresented in the arts will stay that way unless provided with more opportunities and support.

An essential part of being an artist is the willingness to embrace uncertainty, to experiment and take risks, the capacity to recover from failure, but if you’re constantly living close to the bone and every failure is increasingly hard to recover from, you develop an aversion to risk, a reluctance to try new things. You stagnate, and that in turn undermines your career.

And all of this is going to continue as long as there is no incentive for the government, and the industries it supports, to offer some security for artists who’ve provided the economy with all this money and rich creativity. As our work is increasingly commodified, fed into AI plagiarism machines and has its value siphoned into the world of ‘content’, the humans who make all this possible are taking ever bigger hits, leading to short careers, a high turnover of any professional class of artists, and the resultant loss of expertise and experience to Ireland’s creative industries as a result.

In April 2022, the Department of Culture, Communications and Sport invited applications for its Basic Income Pilot Scheme for artists. The number would be limited to 2,000, and you had to meet set criteria to qualify. The payments would not be conditional on any kind of work. A number of unsuccessful but eligible applicants were asked to participate in a control group to help with the evaluation of the pilot. Control group participants were asked to respond to the same survey and data requests as those in receipt of the payment, and were paid two weeks basic income for each of the three years of the pilot scheme to compensate them for the time and effort.

According to the surveys and follow-up interviews with fifty of the recipients, the effects for many were life-changing. In May 2025, Minister Patrick O’Donovan said: ‘This research shows that the impact of the basic income is far-ranging and affects all aspects of recipients’ lives . . . Artists are investing more time and more money into their practice, completing more new artistic output, experiencing reduced anxiety, and are protected from the precariousness of incomes in the sector to a greater degree than those who are not receiving the support.’

The committee of the National Campaign for the Arts said: ‘This qualitative report clearly demonstrates that the BIA has helped to sustain individual creative practice, boost ambition and creative outputs, as well as strengthen artists’ connections to their local communities. In addition, the pilot scheme has supported artists to secure more sustainable housing, address health issues, start families and even establish pension schemes. The findings affirm what the arts sector has long known: the deep precarity of the arts requires sustained, courageous support – support that not only transforms the lives of artists, but also strengthens the society they help to shape.’

The government is now looking into extending the scheme, and beyond what that would mean for the arts in Ireland, there is something more to consider: this is a test run for Universal Basic Income. Providing this scheme for artists is a slightly more palatable version of the concept for those who would oppose UBI. Artists are by definition, identified by their work. And it’s the fear of people not working that opponents play on when they argue against UBI, so providing it to artists is at least something they can get their heads around.

Many of those opponents fail to realize how poverty paralyzes, how it limits education and enterprise, career prospects, how it affects long-term health and the lifespans of the people their precious economy is built upon. Yes, there are some who don’t care about those people at all, but frankly, we can disregard their views. We don’t have to address the concerns of assholes. For those who are simply ignorant of how basic financial security can create a foundation from which you can build a life you might not have had otherwise, how it can enable you to contribute more to society and become a happier and more accomplished person, the Basic Income for Artists is starting to provide solid evidence.

And in the meantime, it would create opportunities for those who might otherwise never break through at all, to have a chance to find their audience, and it can provide much-needed to support to all the artists who enrich the lives of people in Ireland, and who are so often left behind after their careers have been mined by others for everything of worth.

So I’m appealing to the government to make the Basic Income for Artists permanent and comprehensive. It’s time to end the practice of valuing the art, but not the artist.