I’m waiting for a new writing project to kick off, so I have some time to kill, and I want to talk about something that I think a lot of professional creative people will recognize, though each person might experience it differently.

It’s the development of a state of mind that helps us deal with the essentially uncertain nature of this kind of work, and in particular, the state that helps us deal with the negative aspects of it in a way that enables us to keep going when things get tough. I’ve written a separate piece here about that uncertainty, and why it’s an integral part of an artist’s life, but this post is about the defences we can put up in response, how they can help, the cost that comes with them and how we have to stay aware of them because of that.

This overlaps with a number of my other posts, but I haven’t taken a close look at this particular aspect of the life, and it’s becoming ever more relevant as the tech industry tries to commodify the arts and is steadily driving artists nuts, so I thought it was time to explore it. It’s an issue that relates to the public perception of artists, our mental health, imposter syndrome, the longevity of a career, the Basic Income for the Arts Scheme (and Universal Basic Income more generally) and the value of the creative arts to Ireland’s culture and economy.

For most artists, if you work in a commercial form of art, where it’s a day-to-day business for you, it’s common to specialize; you focus on your passions, the skills that you’ve honed and a kind of job you’re confident you can do well, so you become known for doing a particular kind of work. And if you have success in that, it becomes a cycle that reinforces that path, so a solid career tends to be built on those specific kinds of jobs. An author who’s known for writing in a particular genre, an illustrator with a signature style, a musician with a characteristic sound, an actor who plays a certain type of role. It’s a way of finding security in a life that can offer very little.

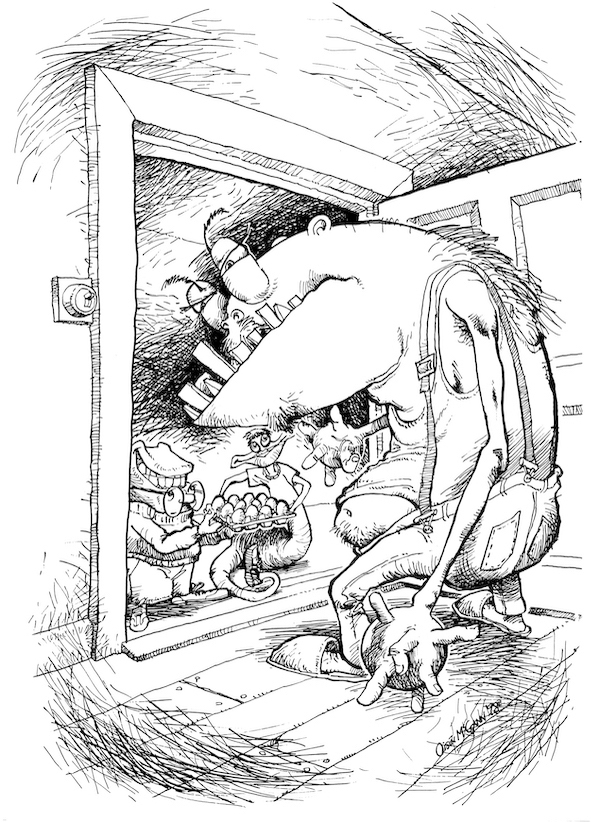

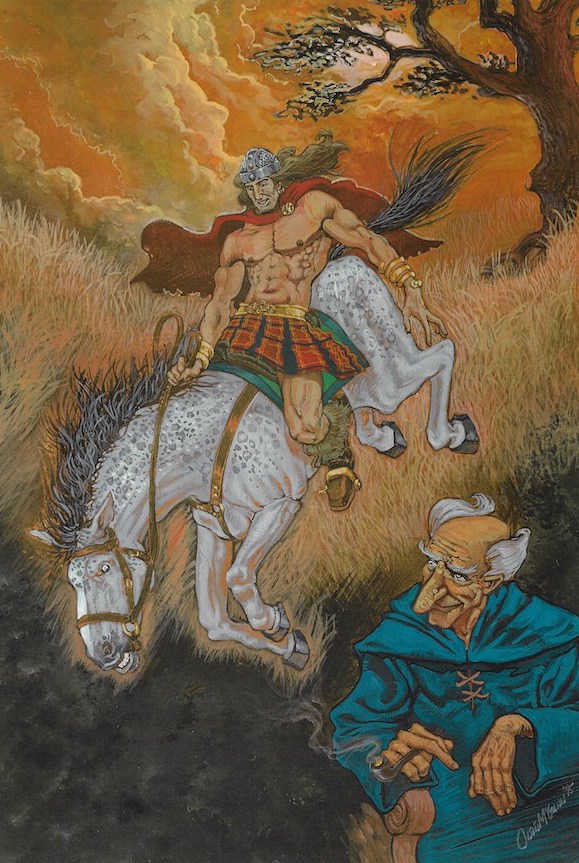

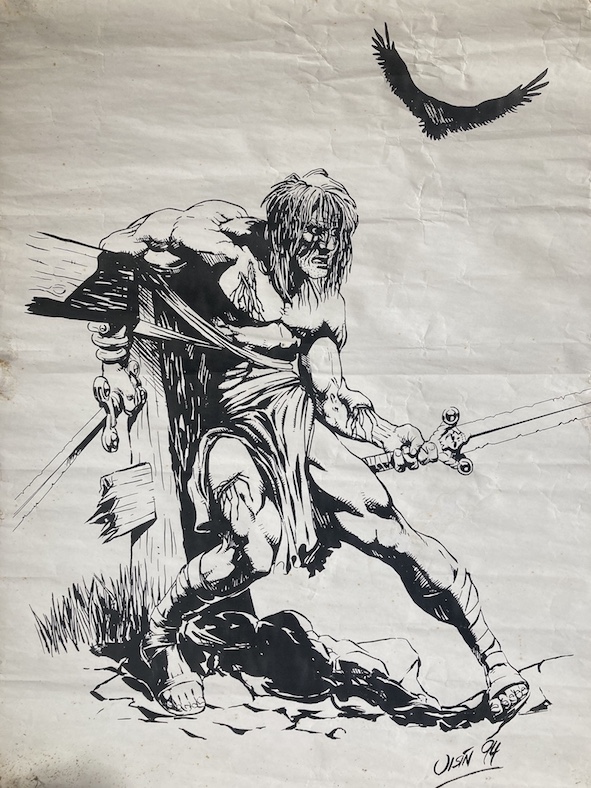

For some of us, making a living can involve casting the net a bit wider: I have been a professional writer and artist for a long time and through a combination of interest and circumstance, I’ve ended up working in a range of roles on a huge variety of projects. On one hand, this can mean that I can take on a wider range of jobs, which you’d think would offer more stability, but it’s countered by the fact that I’m not especially focussed on, or known for, any one thing, which increases that experience of uncertainty.

But for all of us, that feeling that nothing is certain, that we can’t completely count on anything or anyone in our work except our minds, our passion and our expertise, is something we deal with throughout our lives. And learning to cope with that is as much a part of working as a professional artist as the skills you use to make your stuff.

The Myths

There is a perception of the arts that it is populated by, and tends to attract, excessively extroverted and introverted types; passionate but emotionally unstable. Imaginative, idealistic dreamers with their heads in the clouds, who need to be managed by others who are more realistic, more grounded. The stereotype of the creative genius is one who can make great leaps of intelligence and imagination, but who is flaky, inconsistent, living in the thrall of the muse and prone to self-defeating mood swings.

There are also assumptions about how artists are made; the film Whiplash was a particularly egregious example of this. The story of a musician, a drummer, with an abusive mentor, it is a brilliantly executed film that reinforces one of the most insidious myths in the arts – that it takes some kind of traumatic experience to release true creativity, that you must suffer to become a real artist. Suffering, almost to the point of self-destruction, is integral to achieving your ambitions.

If there was one single, almighty piece of horseshit that I could free the arts from, it’s this one.

To be fair, the art world is as responsible for this perception as anything else. The stories we tend to tell about artists are not the ones where someone led a very content life, had great success and died happy. No, we need drama. So we seek out the troubled lives, the most unstable creatives, the worst excesses, the batshit crazy careers, because they’re entertaining – and because those stories are the ones we tell, those kinds of characters stand out in our minds.

A general state of torment shouldn’t be confused with adversity in one’s career. Dealing with uncertainty, running up against obstacles and learning how to deal with failure are constants in this line of work – but prolonged misery is not and should not have to be. There is always a risk in trying anything new and a tension between your ambition and what you can achieve. That challenge is part of the ongoing thrill in what we do. You absolutely do not have to ‘suffer for your art’, but you do have to push yourself, knuckle down and get shit done.

A Reaction to One’s Environment

Another reason for the popular perception of artists, is that they are behaving in a way that may be appropriate to their situation, when they are not in control of that situation, but people outside of their circle are completely unaware of it. It’s a weird career, and it can create some weird circumstances. Anyone who’s self-employed or runs a small business will already be familiar with some of the everyday challenges a professional artist faces, and I’ve written about it at length here, so I won’t dwell too much on it, but to give you some examples that most creative professionals will recognize:

- You will often have to work on something for months, even years without any idea if it will pay or how much it will pay.

- Industries like publishing, music and film could not exist without masses of this kind of free work from which they can pick and choose, often provided by experts with a level of education and experience which would ensure a professional salary in a more conventional profession.

- Ghosting is becoming more common, where you pitch for something and never receive a reply. In publishing, this means that a publisher that has already imposed the condition that they’ll only deal with agents, now may not even reply to agents.

- You also get asked to work on other people’s projects and do events for free – often by businesses that intend to charge other people for that work.

- In most disciplines, there are no set rates for what you do, no industry standards, so you’re constantly having to assess the value of your time and expertise and often, to justify that value to others.

- For most of us, there is no way to enforce industry standards on these things.

- There is no set number of hours to work in a day, nor days to work in a week.

- There is no established career path. If you’re successful in your early life, there’s no guarantee that, even if you keep producing work of the same quality or better, even if you have an established reputation, that you will still be making a living a few years later.

- While learning is an ongoing process for all artists, qualifications can be useful in some specific art careers, but are for the most part irrelevant. In most areas of the arts, you’re judged almost entirely on your work, even when you’re starting out. A life of one-off projects can be very difficult to convey with a CV.

- You may have to chase a client to get paid, even for small jobs, and jump through all kinds of administration hoops. On more than one occasion, I’ve had to fill out a two-page supplier form, submit for Garda vetting, then request a PO number before I could invoice and then waited weeks to be paid, following up with an email or phone call . . . for two hours’ work. I’ve written about the Garda vetting process here.

- You can be an expert in your chosen discipline, but you must then submit to the judgement of people who do not have your expertise, but might well control the environment that you work within, sometimes based on nothing more than ‘they know what they like.’ Artists are almost never working for someone with training or experience in their discipline.

- And everyone’s a critic.

- When you come up with something that’s a success, you can’t do that exact thing in that way ever again. You have to come up with something new. You must do this for your entire career.

Again, all of this is on top of the fact that our work is, by its very nature, built on uncertainty – a fact that we not only have to accept, but must embrace. Creativity is about making something from nothing, starting from absolute scratch. It is our job to fill the void, so you must be willing to face into that void to begin with.

This is why we can seem a bit odd to other people.

But the Arts Are Not as Odd as You Think

There’s a tendency to think of the arts as being separate from normal life, and the practice of them as something we do as a hobby, a side hustle and, only if we’re really lucky, as a career. It can lead to them being perceived as a perk that has to be earned, a luxury we can afford if we work hard enough at something else to justify the time. And as an extension of that, artists are something that society can afford only if the economics are there to support them . . . y’know, if there’s enough real work being done.

Once again, this is a subject that deserves a post all to itself, but let’s just say that the skills that form the foundation of the arts are less the icing on the cake than they are the cement between the blocks of a wall. They represent the everyday actions that hold everything together, they are simply the most prominent, performative manifestation of those skills: A persuasive tone of voice, a sharp retort or a charismatic smile evolve into the performance of an actor. A wail of lament, an encouraging chant or the tapping of a foot become the creation of a song. An attempt to describe something you saw out on the road becomes the painting of a picture. The story you tell of how you figured out how to solve a problem becomes the writing of a novel.

These are essential, everyday social skills, skills that helped form our society and now hold it together, but they have been raised to the level where they can be enjoyed for their own sake, engaged with and analysed – where they can be used deliberately to provoke thought and emotion. They are a constant exploration of what it is to be human; we are experimenting with empathy. And we cannot develop as human beings, as a society, without that exploration. Science, business, politics, religion, sport . . . all of the things that make up our civilization exist within the medium that is human interaction.

But that same society believes that the practice and celebration of these acts should be put aside until the real work is done, even though the arts influence every aspect of a person’s environment. They fill our senses in ways we are often only dimly aware of: the design of a door handle, the colour and font of a shop sign, the most effective sound to use for a tram’s bell to get people’s attention on the street. All of these originated with the skills of an artist.

We are the army of nerds obsessed with every form of sensory input.

Coping With the Shifting Sands

Despite all the celebrated stories of artists with mental health issues, there is plenty of evidence to show that the practice of art helps promote positive mental health. My father, a psychologist, did his PhD in creative behaviour and it was what he believed, and everything I’ve read in the years I’ve been in this business reinforces my conviction that art is good for your mind. In fact, my oldest friend and one of the best artists I know is an art therapist in a psychiatric hospital in London, where he works with patients sectioned for violent crimes. He chose that profession because, as an artist, he got tired of having to constantly submit to the demands of people who had a fraction of his knowledge or ability, and found a job to support himself, that he found rewarding, so that he could create what he wanted in his own time.

I consider myself very lucky that I don’t suffer from depression; I do get depressed at times, of course, but that tends to be due to circumstances – when those circumstances change, so does my state of mind. I can only imagine what it’s like to be followed around by the black dog on top of dealing with the capricious nature of this life.

As I’ve pointed out, a career in art comes with a lot of psychological challenges, some of them unique to the work. One of my brothers or sisters years ago (I can’t actually remember who now), once commented that I didn’t get very excited about my successes, and there are probably two elements to this:

The first is that, from the outside, having a book published, having a launch or being up for an award is a visible demonstration of a success, and it can draw people’s attention on a particular day, so they expect to see your reaction on that day, when the feelings for that project are actually spread over the much longer period it has taken to produce that piece of work. This means that, by the time you reach the culmination of something, you can be feeling a more lasting sense of satisfaction and relief to be finished, rather than a sense of celebration.

The second element is that any career in the arts is usually built on a long series of failures and learning experiences, and you get used to managing the highs and lows of emotion. And the same protective mindset that helps you get over failure can also temper the joy of success – because you know there’s probably still plenty of failure in your future. This may sound negative, but it’s important to understand that you’re achieving this by finding the pleasure in the process as much as – or even more than – the result.

It means that you’re more likely to be happy when you’re working, which means spending a lot of your life . . . happy.

The extreme form of this cautious emotional state can be imposter syndrome. Thanks to a prolonged career, just enough success and an ego that has withstood repeated batterings, this is not something I suffer a lot from now, though I have had it plenty of times in the past. It can have the effect of really undermining someone’s confidence. It’s the belief that, despite your skills and experience, you’re a fraud and that, sooner or later, you’re going to be found out. Much of this springs from the uncertainty of this life: If there is no set way to measure quality or success, it’s very hard to know how you rank among your peers, and society demands that you must be ranked among your peers, even if the drive to create art does not demand it. I can only imagine how much worse the phenomenon of imposter syndrome has become when we are aware of so many other artists from around the world, and see so many of the best of them as we scroll down our online feeds – and you see some of them confessing to feeling like imposters.

Social media, of course, come with positives and negatives. Arts like writing and illustrating can be lonely pursuits, and it’s easier than ever to find supportive communities online, though the enshittification of these platforms is having an impact on that, as it becomes increasingly difficult to connect with people without having your data harvested or being bombarded with ads or propaganda. Also, audiences you’ve built up over years now hardly seem to see your posts unless you’re willing to pay for extra reach. We helped these companies build their platforms with our content and now most of them are squeezing their dwindling users for whatever they can get out of them.

We stay on, however, because if you’re on your own at home for most of the day, this is the closest you get to having workmates and talking shop.

And by doing so, you get to see and hear about the problems that other artists are having, and you can share yours, which can help, in that you feel that there are people who can empathise with you. But it can also leave you feeling that, if everyone’s having the same problem, then maybe there’s no way to escape those problems. It can feel like a real uphill struggle to make a living in Ireland, and you wish you were in a bigger market, and then you see people in the UK who have much bigger audiences and higher profiles than you, people you may empathise with, having their businesses tanked by Brexit. Or people in the US asking for donations to pay their rent or running GoFundMe campaigns to pay for basic medical procedures to . . . you know, stay alive. It’s a reminder that we’re running a race against our physical health too, hoping that if and when something happens, you’ll be able to take the time off and have the resources to deal with it.

Let us not say any more about all the other shit we get exposed to on our feeds, but that has an effect too.

The rise of ‘AI’ text and image generators has thrown the issue of artistic process into sharp relief. Yes, this tech is a massive threat to artists, but it has also highlighted the distinction between the process and the result, because it’s now possible to produce an image or a piece of text without experiencing the making of it. We’re seeing the rise of a breed of ‘artists’ who don’t want to spend their time making art, which is absolutely fucking mystifying to those of us who do. It’s not a ‘tool’ if it removes you so far from the work that you’re basically just placing an order. That doesn’t make you an artist, it makes you a client. We are not looking for ways to avoid the work. We’re here for the work. There isn’t something else we’d rather be doing.

I’ve written a longer piece about this too, for the European Writers Council.

Now, when you go looking for a reference image online, you find a growing proportion of LLM-generated images, a flood of pictures that can be generated faster than any artist can work, creating an ever-bigger swamp the rest of us have to wade through. And now the people who make these images are expressing frustration at the lack of satisfaction it provides and that they can’t get people to take an interest in them. Hilariously, some of them sneer at artists who object to the mass breach of copyright used to create this material, while at the same time complaining about people ‘stealing’ their prompts.

Unless you’re an experienced scam artist, there is no living to be made using this stuff, and certainly no long-term career to be had, because you haven’t developed the other survival skills, and the self-sustaining mindset, that come with the job.

Suffice to say, coping with all of these issues contributes to a mental version of battening down the hatches when things get tough, as I’ve mentioned in other posts, and this in itself is something you have to be conscious of, as that protective state of mind, your emergency mode, can become a lasting condition. You become risk-averse, you avoid making long-term plans, you prioritize immediate needs over more long-term concerns like your health, you avoid going to your doctor or dentist because of the potential cost, you don’t have hobbies that cost much money, you don’t take holidays and you avoid direct debits or any bills that you absolutely don’t have to have, because the world works on the basis of regular payments and you don’t get paid on a regular basis.

While this can be a challenge when you live alone, the stakes are much higher when you have a family, you can’t just go into survival mode and cut your spending or your time off down to nothing. If you’re averse to planning things far in advance, or putting yourself in a position where you might have to spend money when you don’t want to, or you don’t take time off because you’re afraid of missing a deadline or an opportunity, then it can affect everything from vacations to everyday activities with your kids. You signed up for this – your family didn’t.

There’s an impact on your work too, because you stop experimenting. You worry too much about trying to predict what kind of work will sell or will get more attention online. Your creativity can start to stagnate and this too can contribute to knock-on effects on your health. It becomes a vicious circle.

Obviously, money is a big part of it. The ‘AI’ boom represents an extreme caricature of the arts world, where the money from both business and government funding feeds the system, but much of it is soaked up before it reaches the artists. Pretty much the only people in full-time employment in the arts, with any financial security, are the ones who work in the organizations that artists interact with. And though I understand the reasoning, that you can’t fund all the artists all the time, so you need structures in place to support specific projects, it can often feel like our work is valued, but our lives are not. And Ireland is a lot more supportive of its artists than many other countries, not least because we have the Artists’ Tax Exemption which, quite frankly, is the main reason a lot of artists choose to stay in the country rather than emigrate to somewhere with better prospects – which, of course, is why it was introduced.

There are strict limits to the exemption, and most of us have to take on non-exempt work to survive anyway, but if there’s one piece of evidence of our value to the country’s finances versus our proportionally low pay, it’s that Ireland makes more money off our work than it would taxing our incomes.

Despite the supports available, most people just can’t cope with the insecurity long-term. Financially and emotionally, there can be too great a toll, and if there’s one key argument for the Basic Income for the Arts Scheme (and Universal Basic Income more generally), it’s to give people a secure enough base that they can strive without the fear of falling too far if they fail. For artists, this is especially the case, because for most of us, there is no secure employment to be had in our line of work. There is hardly a time in most of our careers when we’re not at risk of the total loss of that career and when things do get tough, there is rarely a safe option we can reach for within our chosen profession, only other risky ones.

Even our social welfare system is not set up to help all the self-employed people that contribute so much to our economy. If your income drops so low that you can’t support yourself, you have to stop being self-employed in order to claim benefits that you’ve been paying for over your whole career. I don’t think it means you have to cease trading, but you do have to reach the point where you’re absolutely desperate before you can ask for the minimum amount of help, so it seems like the system is undermining your ability to get back on your feet again.

Having a secure financial base (even a low one) to work off would enable Ireland to maintain a professional class of artists, ones who aren’t constantly worried about how they’ll pay the rent or mortgage next year – or next month. Which is important, if you want to maintain the film, TV, theatre, animation, publishing, music, games and craft industries, all of whom rely on reservoirs of creativity, experience and initiative to be available to them – none of which they have to pay for until they’ve taken their pick.

It would certainly help the mental health of people who are not expected by society to have sustainable careers, but whose creative work is considered a rich resource to be mined by all the businesses that have based their existence upon it.

Staying Happy

Raising those emotional shields can be unavoidable when money is the problem, but even just sticking with the same kind of work for years on end can wear you down too. It can be the intellectual equivalent of the depressed animal in the zoo, pacing back and forth in its small enclosure. I often fall into the habit of only creating stuff that fits in with what I’m doing for the job, and I have to remind myself why I got into this line of work. I have a busy head, and it can be easy to confuse thinking a lot with being productive, particularly when you need to watch a couple of hours of a film (nothing too thought-provoking) just to switch your brain off at night.

If there’s one thing I’ve always been thankful for, it’s that I always knew what I wanted to do – make stories. Maybe not in one specific form, but throughout my life I’ve been making constant course corrections to keep me pointed in more or less the right direction. That compass has always served me well. And even though I now do this as my job, recognizing when I need one of the those course corrections is something I’ve paid attention to. And this applies, even if it’s a ‘staying happy’ move, rather than a career move.

Art’s value to mental health lies in the fact that you’re doing something for your own pleasure, but something that is also a form of expression. It’s something that came out of you, to be witnessed by other people. You’ve made something that acts as a connection to those around you. There’s a vulnerability there, an emotional investment, because even if you’re not doing it for an audience, other people’s views of the work will matter to you. It might just be a misshapen little pottery bowl, but you can be hurt if they criticise it – or feel uplifted if it’s appreciated, if it gives pleasure. Once you make it your job, you have to clamp down on that vulnerability to some extent or it can become overwhelming, and people can take advantage. It’s your living now, you have to get paid. We’ve got a mortgage on our house, three kids and all the bills that come with them. I have a responsibility to my family to maintain my business, the longevity of my career, so I can’t be sentimental about the things I make.

Even so, the need for expression is still the main thing driving the work. And when it’s not, then I have to make a course correction. This job is too hard to do if you don’t love it. However, one of the things about doing this for a living is that you come to rely on things that have succeeded before, and pulling away from that path can be unnerving. Not only could it mean the possible financial cost of failure, in terms of loss of investment or especially lost time, but by getting emotionally involved in your work again, you’re leaving yourself vulnerable to the judgement of others. It also takes extra effort – doing something new, starting something from scratch, always does.

The more that inertia has set in, the more you need to change course, the more you might question the need to take that risk. Ironically, artists with years of experience can end up suffering from the same hesitation and insecurity as someone who’s just starting out. You know you need to fly again, but that caution that has been so vital to your long-term survival has made you too scared to jump.

And in truth, it’s not even achieving flight that really matters, it’s knowing you still have the nerve to jump, to find the joy of release. Sometimes you just have to say ‘Fuck it!’, and go. After all, it won’t be the first time you’ve crashed, and it most certainly won’t be the last.

A couple of months ago, I got that itch. Most of the books I’ve published over the last few years have been commissioned; I’ve been working on a lot of stuff on climate change and I needed to do a skid-turn – I wanted to put out a different kind of book.

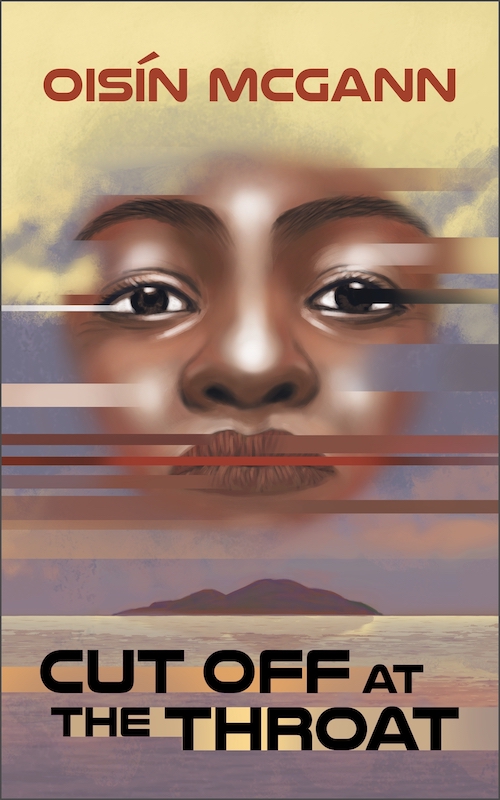

Years ago, my agent (who I’ve now been with for about twenty years), refused to pitch a novel I’d written. It did have a pretty dark theme, but she’d never done this before and it was real blow after all the work I’d put into it. I ended up shelving the project. Then in June of this year, I decided to rework it a bit and publish it myself. I’ve self-published before, and given all the tools and services available for this nowadays, and the fact that authors do most of the marketing for the books anyway, I figured why the hell not? I couldn’t put any real money into it, but at least it would scratch that itch – I’d be taking a running jump again. It was originally entitled Pass by Mouth, but I published it as Cut Off at the Throat.

There turned out to be a whole lot more to the process than I’d originally expected – I’m going to do a separate blog on that (feels like I’ve got a separate blog for everything on this post) – but damn, it felt good to be putting it all together myself, and there was a satisfaction in seeing it out in the wild that I hadn’t had for some time. You can find it here.

The funny thing was, although I was doing this in order to take a creative leap, I didn’t actually do a lot of writing on it; apart from some light editing, the story was pretty much ready to go, but the completion of it, everything from illustrating the cover to setting up the print file, was cathartic. I’ve had another book sitting around for a while, a very different one again, and now I’ve decided to get my arse in gear and finish off that one too. This one will have illustrations and I’m really looking forward to them.

This is not an easy life, and yet I do feel privileged, not just because I’ve been able to make this my career when so many can’t, but because of the combination of circumstances that have given me the mental stamina to keep at it. It’s a quality that’s common in people who’ve been in artistic careers for a long time; either they had it coming in or they learned to develop it, and at the root of it is a love for the work – not just the result, but the process.

The joy of making stuff gives you a resilience, so you can keep picking yourself up, but over a long enough timeline, you can end up with a mental state that’s much more resilience than joy. And sometimes the only remedy for that is to crack open the armour and make yourself vulnerable again.

We all started out with that vulnerability and it didn’t stop us then, so it shouldn’t stop us now.