Let me tell you about the weird business that delivers art into our lives, and what it means for the long-term careers of artists. This piece was prompted by yet another newspaper article on how authors are paid, and the inevitable reactions from the ‘people-would-pay-if-it-was-worth-it-to-them’ brigade, but much of it applies to the arts more generally.

First, it’s important to realize that the creative industries make a major contribution to the economy; about £124 billion in the UK and as much as €5 billion in Ireland’s much smaller economy (it’s hard to find an accurate figure).

Despite this, there are hardly any secure, full-time employment opportunities for artists in either country – or in most other countries. To be clear, there are plenty of full-time jobs in the creative industries, but most of them are to do with managing, promoting or distributing the work of artists. The artists themselves cannot expect that kind of job security.

The vast majority of artists are self-employed or do contract work, which means that, although there are entire industries based on the work we do, they never have to take any responsibility for the livelihoods of the people they are entirely reliant upon.

It would be more accurate then, to think of artists as a natural resource to be mined by others, rather than as valued workers in an economy. Let’s take publishing as an example: I want you to think about how a book ends up on your shelf, or on your e-reader.

For the sake of simplicity, I’m going to keep the numbers really basic and very conservative: Let’s say a publisher gets a thousand novel submissions a year, but can afford to publish ten new authors. And let’s say that one of those books is a moderate hit. Nobody will be able to tell you with any certainly which one of those books it will be.

For that one hit, there were a thousand books written. If we’re kind and we say that a novel takes six months of solid work to write, then that’s six thousand months of work produced. The publisher has paid for 60 months of that.

But despite the advances that make headlines, in most cases, they almost certainly haven’t paid a living wage for that work – probably only a fraction of that. I’m not trying to paint publishers as villains here; publishing is a risky business, especially if you’re a small outfit, and for most of the people who are employed in it, it’s not very well paid, but by far the biggest proportion of the risk on any book is taken, not by the publishers, but by the artists.

The publisher can take their pick from six thousand months’ worth of work, knowing they only have to pay an advance for the books they want, and that advance will almost certainly not reflect the amount of work that’s gone into each book.

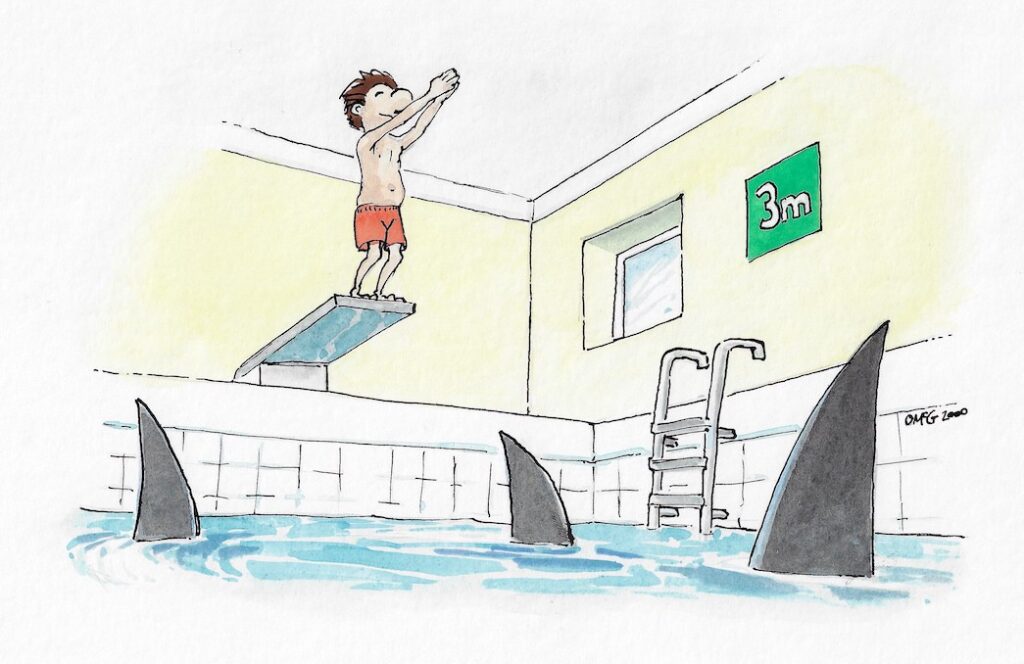

The rest of that financial risk lies in the time and effort invested by the artists. Most of us understand this going in. Unless you have a contract for a book, you’re doing work on spec. Depending on where you are in your career, your prospects of ever getting paid for that work can vary wildly.

On top of all that, for most books, the writer is the main form of marketing and advertising. We’re expected to go out and do events to help sell the book. The demand that we spend more and more time online, contributing work for nothing is a common feature of the job.

And if the book doesn’t sell, there’ll be an implication that it’s because the author didn’t do enough. This is implicit in the increasing move towards celebrity books. Authors are supposed to provide publishers with ready-made audiences.

But you take the risks so you get the rewards, right? You do the far greater proportion of the work, so you get the biggest cut? Right? Well . . . no. Typically, the author gets the smallest cut after everyone has taken theirs: the retailer, distributor and publisher. This can vary a lot between the small operations and the big ones, and gets more egregious at scale – check out the book Chokepoint Capitalism by Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow.

There are plenty of supports for artists from the likes of the Arts Council and the arts offices in local councils. Ireland has seen a big increase in financial support for the arts over the last few years. But again, the only secure employment is in *managing* those resources, not in making art.

Artists have to apply to those organizations for every payment they get – more work – and here too, the odds of getting paid are against you. There’s no form of income you can rely on, year after year.

There is a tiny fraction of artists who are successful enough to make them independently wealthy. There are some more who manage to make a living, but that’s increasingly difficult to maintain over a long timeline. For all the rest, they can only dream of reaching that stage. All but a few writers have to make their living at something else, providing the publishing industry with a steady supply of free work, from which it can choose as it wishes.

Unlike everyone who’s *employed* in the creative industries, as a self-employed artist, you can’t look forward to some kind of support at the end of your life, if you put in enough time and work, beyond the same state pension that everyone gets. Every challenge you face, every hit you take, you deal with on your own. It is a system of attrition.

It means that the more committed an artist is to their career, the greater a risk they’re taking with their financial security. It’s how the arts industries can keep rolling along year after year, because they’re on a road built on thousands of collective years of free labour, leaving used-up artists in their wake – artists who have insulated them from the greatest risks involved in their business.

And this is going to continue as long as there is no incentive for the governments, and the industries they support, to offer some security for artists who’ve provided the economy with all this money and rich creativity.

As our work is increasingly commodified, fed into AI plagiarism machines and has its value siphoned into the world of ‘content’, the humans who make all this possible are taking ever bigger hits, and the arts organizations and publishers who will stand out for us, who will maintain their credibility, will be the ones we feel have our backs. We will remember who they are.

Ireland took a big step in recognizing this issue in 2022, when it introduced a pilot scheme for a Basic Income for the Arts with a budget of €25 million, where €325 a week is paid to 2,000 artists and creative arts workers for 3 years. During the application process, you had to prove you were a professional, practicing artist, and there were various ways of doing this. There is a survey as part of the scheme, and a control group is included who don’t get the payment, but are paid two weeks each year to provide the survey with the equivalent information.

The artists I’ve heard talk about being on the scheme have described it as life-changing. It has allowed them to plan ahead, experiment, take better care of their health and it’s had major, beneficial effects on their mental health. For obvious reasons, there are calls to extend the reach of the scheme and make it permanent. Another knock-on effect is that it’s a very concrete test of the benefits of Universal Basic Income.

The government will be making decisions about that soon, and if you’re an artist in Ireland, keep your eye on what’s happening. The power is not all in their hands. We can make things better. We are the artists. We are driven and stubborn and imaginative and self-employed and there’s nobody we have to work for. We got into this because we wanted to do things our way. Maybe we should remind ourselves of that more often.