I’m borrowing the theme/title from Trinity Week for this piece, partly because of the great event I got to do with Philip Reeve and Conor Kostick last Tuesday, and partly ‘cos it fits nicely with the other stuff I want to talk about . . .

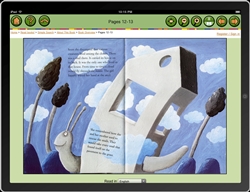

An article I read recently on Publishers Weekly about new apps for the iPad and the iPhone is the best one I’ve seen so far about how children’s publishers are becoming pioneers into all the new formats that are exploding into existence.  This article is about Apple’s tablet, but it’s what is being created for the device that’s interesting, with applications that still centre around reading, yet offer animation, audio, interactive text and activities such as digital painting, puzzles and games. There are also services like the International Children’s Digital Library, offering its content from creators all over the world for free as apps.

This article is about Apple’s tablet, but it’s what is being created for the device that’s interesting, with applications that still centre around reading, yet offer animation, audio, interactive text and activities such as digital painting, puzzles and games. There are also services like the International Children’s Digital Library, offering its content from creators all over the world for free as apps.

Marie-Louise Fitzpatrick, one of Ireland’s best picture book creators, sent me this link she found for ‘Alice in Wonderland’ on the iPad. They’ve done a lovely job on it.

But I’m still a great believer in always bringing things back to basics when it comes to developing essential skills. All the best digital artists learned their trade with pencils, paper and paint, working the old fashioned way first. Before it all becomes buttons and styluses and touchscreens, kids should get crude and mucky and feel the textures under their fingers and get the smells of the different materials. It’s bad enough that all the drawing they see on television is done with a marker (or even worse, on a computer screen) without making any mistakes. It makes it look like a magic trick and leaves them with a terrible impression of how art is supposed to work.

Writing should be approached the same way. A good story shouldn’t have to rely on gimmicky features to work; those features should enrich the core experience, not substitute good storytelling. And the same applies with learning to read.

Niamh Sharkey – whose wonderful book, ‘The Ravenous Beast’ has been released as an app – sent me this link to an article by Sharon Glassman on the Publishing Perspectives site.  It features a discussion with Antonio Faeti, President of the Jury for the book prizes of Bologna Children’s Book Fair, and is about the how the world of picture books is evolving, and the importance of these books to the new generation of kids, with regard to equipping them to deal with an increasingly complicated world. I thought this bit was particularly interesting:

It features a discussion with Antonio Faeti, President of the Jury for the book prizes of Bologna Children’s Book Fair, and is about the how the world of picture books is evolving, and the importance of these books to the new generation of kids, with regard to equipping them to deal with an increasingly complicated world. I thought this bit was particularly interesting:

‘He cites a study at the University of London that prescribes exposing infants to picture books starting at five months of age as a way of helping them “manage a high-stimulus society.”

‘A brain formed on multi-layered images will be more prepared to tackle the mental double-espresso of multi-tasking in years to come, this argument says.

The point ends with:

‘The ability of beautiful books to prepare infants and children for a high-tech life adds a new dimension to bookselling.’

It’s certainly an argument that strikes a chord with me. This technology is part of our world now, which means that developing the skills and the maturity to use it properly is all the more important. But I’d be a little concerned that children start to see books, or any large collection of text, as more and more like vegetables or vitamins (a positive comparison in the article). Faeti goes on to say:

‘A brain formed on sound bites and headline news doesn’t have the skills to dig deep and ask, “How does these events compare with the original ones? How much of this news is hype and how much is reality?”

“Generations are growing up who can’t distinguish,” warns Faeti.’

That’s my single biggest concern if we can’t produce the stuff that can hold these kids’ attention and extend the attention spans. Speaking of holding kids’ interest, the event with Philip Reeve and Conor Kostick in Trinity College last Tuesday went very well. I got an extra treat in the form of a mini rostrum camera that could film a drawing I did and display it on the huge screen behind us – what one person referred to as ‘drawing live’. I normally have to use a desktop easel, or a flipchart and they’re no good for big crowds. We had about three hundred and fifty in the lecture hall that day.

That’s my single biggest concern if we can’t produce the stuff that can hold these kids’ attention and extend the attention spans. Speaking of holding kids’ interest, the event with Philip Reeve and Conor Kostick in Trinity College last Tuesday went very well. I got an extra treat in the form of a mini rostrum camera that could film a drawing I did and display it on the huge screen behind us – what one person referred to as ‘drawing live’. I normally have to use a desktop easel, or a flipchart and they’re no good for big crowds. We had about three hundred and fifty in the lecture hall that day.

I’ve done a bunch of events with Conor – we both had our first novels published by the O’Brien Press around the same time. He’s a good friend and is always interesting to listen to. He has a huge interest in the blurring of boundaries between reality and virtual reality and the possible social consequences. Philip is one of my favourite authors, and it was a nice to discover he’s a sound guy too, articulate and passionate about his work. And as interested in history as he is about the future, which is one of the elements I think gives his sci-fi stories such a rounded feel.

Thanks to the organizers of Trinity Week and the gang at Children’s Books Ireland for setting up the event, and to Karl Burke and Trinity College for providing the photos.

Thanks to the organizers of Trinity Week and the gang at Children’s Books Ireland for setting up the event, and to Karl Burke and Trinity College for providing the photos.

The interview between Philip and Robert Dunbar that evening, attended by many of the great and good of Irish children’s books (aka The Usual Suspects) went down very well, and the whole day emphasised the current craze for accessible, innovative science fiction. But that demand is also, as Philip pointed out, for sci-fi that is not only about ideas, but characters too. If ‘mainstream’ science fiction has a common flaw, it’s that the concept often crowds out the character and storytelling.

That’s a luxury you can’t afford in young adult books – story is king – so I think that’s why young adult or ‘crossover’ books are becoming so popular with grown-ups. Particularly as real life starts catching up on science fiction, and real technologies become more and more electrical, virtual, invisible, intangible – harder to understand and relate to. Technology is reaching the point where it is almost magical to anyone without a relevant education. I don’t think this is a good thing, but it’s hard to know enough about everything.

I believe that, as the effects of that technology on our lives and its integration into them become increasingly hard to separate from life’s fundamentals, it will take ever more clever storytelling to explain it, investigate it, make it understandable and still spin a good yarn to engage a reader on an emotional level so that they stay interested.  I’m not a scientist, a computer programmer or an engineer, although I have a very amateur interest in the effects of these things on our lives.

I’m not a scientist, a computer programmer or an engineer, although I have a very amateur interest in the effects of these things on our lives.

But we will need writers who really know their stuff, and can also turn these issues into gripping stories (a rare mix), to help us understand our fast-evolving world, give us a structure for lives within that world, and help us keep things in perspective. ‘Cos that’s what great stories do.

And just to sign off on this post, here’s a link to ‘Pixels’, by Patrick Jean, a spectacular short film that should bring a smile to the face of anyone who grew up in the 8-bit, chunky pixel era of Space Invaders, Pac-Man and the unfortunately named Pong. And if you didn’t, you’ll probably like it anyway.