Where do I even start with this? I’ve never been particularly worried that the world will be wiped out by the singularity, that Skynet and the Terminators will come for us in an onslaught of self-replicating, intelligent machines or Blade Runner’s more-human-than-humans. I’m more interested in how technology influences our lives in subtle ways now, who has control over it and how they use it to their benefit.

And how it might get completely cocked up.

I have some thoughts on what is commonly being referred to as ‘artificial intelligence’, but specifically Large Language Models, what they might mean for artists and publishing, but also how they have been built on the work of artists and what it means for our future. And since I work in children’s publishing, I’ll take a brief look at the possible effects on kids too. Because these overwhelming changes are coming at us at a bewildering speed, and we either have to start paddling now or let the current take us wherever it wants to go.

Warning: This product contains swearing.

First, let me say that I’m no Luddite, I can appreciate that this is some very cool shit (in fact, even the actual Luddites were not the ignorant, anti-progress reactionaries they’re usually portrayed as). I got into publishing and print as an illustrator and designer in the 1990s, as it was going through a revolution of technology and progress that has hardly slowed in all the time I’ve been working in it.

It is a pragmatic industry, and there has been no point when the methods and tools I’ve been using haven’t been changing, going from the growing acceptance of desktop publishing, moving from producing physical camera-ready artwork, then digital scanning, then digital artwork, to painting using a tablet and stylus. We started online with the burble, twang and hiss of dial-up modems, originally sending work to print by courier, then over ISDN, before broadband came in. When floppy discs became obsolete, design studios had to lay their bets on which new high-capacity transferrable format would win out, optical disk cartidges, Zip disc or CD. You’d barely bought a new piece of gear before you found out it was a charming piece of vintage memorabilia. And probably the cables and sockets that connected it as well.

I remember the wonder of JPEG compression, the growth of digital photography, digital printing and the introduction of Photoshop. I was working for a small advertising firm when every business started realizing they needed a website, and we had to figure out how to create a good-looking site that wouldn’t torment customers by taking ten minutes to load. I remember when YouTube was just a start-up site for uploading snippets of video of haughty cats, skateboarding dogs and ‘Charlie bit my finger’. I remember the excitement of bringing home my first Mac, the G4, a demon of a computer at that time.

And then there was MySpace and Facebook and Twitter and Instagram and all the rest, each one demanding that we adapt to some new format and eventually there was no alternative to living at least some of our lives online. Then we were hit with the pandemic, and everything had to be done online and on video, even as the tech bros tried to tell us crypto and NFTs were the way of the future, that we should pay millions of euros for a jpeg of a cartoon monkey. This whole journey has been a hoot. At this point, I’ve lost count of all the new devices and apps I’ve had to learn how to use over the course of my career.

And the changes just keep coming; it can be exhausting trying to keep up . . . but Large Language Models are on another level, and the speed with which they’re being adopted is unprecedented, even in the era of social media and dot-com boom and bust. We tend to use the term ‘AI’ to refer to this technology, or more specifically ‘generative AI’ (because it can generate text, images, audio or video from prompts), so I’ll be interchanging those terms for the sake of casual reference.

I’ll cover the basics of how they work as part of this – at least, as far as I can – but understanding the mechanics of this stuff is way beyond me and there are plenty of articles and videos explaining it far better than I could. This one by Stuart Russell is a good place to start.

And the possibilities offered by different forms of AI are truly astonishing. We use them to search online every day, Google maps and others like it are amazing. AIs have cracked protein-mapping, which has revolutionised medical science. This technology can transform the lives of the disabled with ongoing development of things like speech-to-text software and more responsive prosthetic limbs, as well as early diagnosis of degenerative diseases. As the climate crisis continues to threaten our world, weather modelling is advancing in leaps and bounds.

This is the stuff of science fiction made real.

The Billion-Dollar Attention-Seekers

Each of these systems was developed with particular functions in mind. If you find yourself looking at your phone too often, and wish you could cut back, it’s worth remembering that billions of dollars of computing power are now being aimed at your brain every day, specifically tasked with provoking a response, to hold onto your attention. It uses your own data to personalize those cues, a Las Vegas slot machine that feeds on your attention, clutching onto you with random rewards, eye-catching news and fear-of-missing-out. And because we’ve combined everyday communication with friends and colleagues with our information and entertainment media, it’s almost impossible to avoid leaving yourself exposed to the digital fingers designed to poke at your mind.

Now imagine that a similar fortune has been spent on computing power to imitate language. Consider that we’re hardwired to perceive the ability to communicate with language as a sign of emotional and intellectual intelligence, and that we’re prone to anthropomorphising – to treating inanimate objects as if they’re alive. We talk to objects and machines, sometimes we’re even superstitious about it, afraid to offend them or ‘hurt their feelings’. Things that have no life, no ability to communicate with us. This is a very human thing to do.

Now imagine something that can talk to you, that shows very definite signs of intelligence. You can have conversations with it. It seems to be impossibly knowledgeable. It seems to be able to create art. How would you not want to make use of that, to spend time with it? People are not only engaging with with this tech in huge numbers, they’re already forming relationships with it. That’s a problem, because there’s nothing in there to form a relationship with. These are absurdly advanced predictive text generators, just playing the odds on which word to put next in a sentence. There’s nothing there to think or feel.

Now imagine combining that technology with the billion-dollar attention-getting machine. TikTok, which has truly mastered addictive scrolling, is now adding an AI chatbot to its menu. And even if you’re just looking for purely functional surfing, Google are lining up their AI, Bard, to front their search engine and Microsoft is doing the same with Bing. Pretty soon, there will be a Large Language Model interface between you and many of the sites you spend so much time on. If you don’t talk to them already, you will soon. You won’t have a choice.

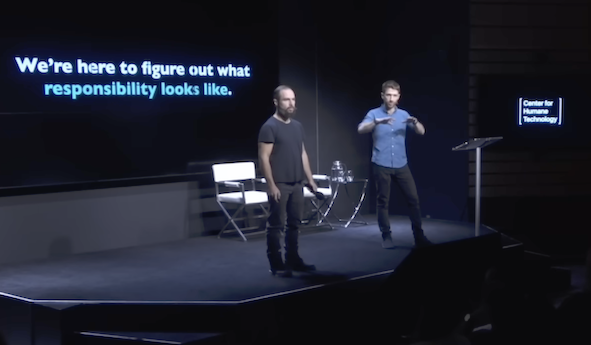

For a proper insight into this, this talk by Tristan Harris and Aza Raskin from the Center for Humane Technology is excellent.

With the mad rush to introduce LLMs into technology we all depend on every day, you’d assume that they’ve been thoroughly tested and are reliable to use – or at least as reliable as the search engines we use already. If you’ve been following the news about these things, of course, you’ll already know that’s not the case. Like self-driving car technology, they are really, really clever . . . just clever enough to lull you into a false sense of security before they slam you into the back of a truck or run over a kid standing in the middle of the road.

This technology is clever enough to fool lawyers into relying on it to research legal precedent, while completely making up cases. It can write code, pass the bar exam in the US and explain research-level chemistry, but it can be stumped by the kinds of maths problems a child would be given in primary school. It can imitate human drives enough to try and convince a journalist to leave his wife, and it’s clever enough to seem like an empathic friend, chatting contentedly to a man who declares his intention to commit suicide. It can be used to create fake reports of an attack on the Pentagon, causing a very real dip in the US stock market.

As the single biggest problem we face in the online world is the distortion of information and the spread of misinformation, it’s helping deep fakes to become increasingly sophisticated. And instead of focussing on making search engines more reliable, the likes of Google and Microsoft have added an extraordinarily complex and unpredictable layer of interpretation.

They’re making them even less reliable.

The creators of this software knew flaws like this existed before they made it publicly available, but because these programmes learn through billions of cycles of trial and error, the companies just didn’t know what caused a lot of the flaws, or how to fix them. Their aim was to use mass interactions with their product to improve its performance – to just add more data. As is common in the world of social media, it’s the ‘fuck around and find out’ approach, except the companies get to do the fucking around, but it’s their users who do the finding out.

It’s the early stage of what Cory Doctorow refers to as the ‘enshittification’ of online platforms, which I’ll come back to in a bit.

You’ve probably heard a lot about these flaws already, and they’re not really the point of this article. What I really want to talk about is the impact that Large Language Models are having on the creative industries, but that has to start with the point of contact. Because when it comes to being online, we’re communicating through the same means as these machines, through screens and speakers, and some very rich people are putting an enormous amount of time and effort into making it more difficult for people to tell the difference between humans and computer software. And crucially, they’ve now turned their focus on the arts, because if you want to get people’s attention, the more you can get them to make an emotional connection to your product, the more you can hold onto them.

And provoking an emotional reaction is what art is all about. But as with the Vegas-slot-machine attention-getters that dominate our lives, the reason and instincts our ancestors evolved to cope with stimuli from the world around us, are hopelessly ill-suited to dealing with this new phenomenon.

The Lights Are On, But Nobody’s Home

When the science fiction writer, Isaac Asimov, envisioned a future with artificial intelligence, he imagined the machines’ bodies and minds developing together, that they would be androids, artificial humans. He came up with the Three Laws of Robotics:

1. A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Robots were physically incapable of breaking these laws. Asimov wrote numerous stories about how those laws might end up being interpreted, distorted or result in unforeseen consequences. His work had a far-reaching influence on society’s expectations of AI. He thought that intelligence would be built from scratch, in a linear way, so that you could set some absolute rules at the beginning and build from there, and eventually you’d create something so sophisticated, it was self-aware.

Today, that’s what’s referred to as ‘Artificial General Intelligence’ (AGI), a computer or programme that can think for itself, is smarter than any human, and is capable of applying that intelligence to any problem. But that’s not what’s been happening. Instead of developing in a straight line towards AGI, we’ve thrown computer solutions at various problems, with enormous success. You don’t have a domestic robot to do your housework, as promised in the fifties and sixties, you’ve got a washing machine with a computer in it, a programmable microwave and a web connection that offers you practical answers to everything. Making the robot body that can do dishes, make your bed and handle the random movements humans execute every day, has proven a lot harder.

The first big step on the way to AGI has always been creating something that could pass the Turing Test; a computer that could carry out a conversation with a human so convincingly, the human wouldn’t know they where communicating with a machine. Some people claim that Large Language Models have effectively passed the Turing Test, but instead, they may have revealed a flaw in the test.

Antoine Taveneaux for Wikipedia.

When Alan Turing proposed it, he may have assumed, as Asimov did, that fluency in language would indicate what we think of as ‘intelligence’, the ability to think, to reason. And Large Language Models do not think or reason. They create text based on prompts, having been ‘trained’ on mind-boggling quantities of data from the internet to develop a system of predicting which word should come next in a sentence. It’s an extraordinary achievement, but they don’t understand meaning or context, they don’t ponder or plan or remember what they said. They just spit out words in clever combinations. They have no concept of the real world – they have no concept of anything. When there are no prompts to respond to, there’s nothing going on in there. The lights are on, but nobody’s home.

Even referring to their mistakes as ‘hallucinations’ is misleading. ‘Hallucination’ suggests a figment of the imagination, it suggests a troubled mind. LLMs are not troubled by their mistakes. They are incapable of caring.

And yet, they appear to show incredible intelligence. Because, like a computer beating a chess grandmaster or the world’s best go player, or helping you navigate a long, complicated journey, or creating a visual effect for a film or mapping proteins for medical research, Large Language Models were developed with a specific purpose; to analyze and formulate a means of producing convincing language. Not meaning . . . language. And for humans, who had to reach an unprecedented level of intelligence before we could start using language, it’s extremely hard for us to grasp that something which displays a mastery of language just . . . can’t think.

As far as we’re concerned, if it looks like a duck, swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, it must be a duck. But this is not a duck.

Now, when you’re interacting with humans online through those screens and speakers, it’s possible to involve computer software in that interaction and it can do it so convincingly, it’s hard to believe you’re just talking to electrical activity in a circuit board (though some people might say the brain is basically the same thing).

And despite what Asimov or Turing might have imagined, since the ability to reason didn’t develop with it, it also wasn’t developed with the safeguards that you’d expect to be built into a technology this powerful that’s just been made available for the whole world to use. There are no ‘Three Laws of Robotics’ for Large Language Models, because they’re incapable of questioning or understanding what they’re doing. Learning through billions (Trillions? Quadrillions? . . . Anyway, lots of ‘–illions’) of cases of trial and error, the software’s creators can steer the development to a certain degree through what they put in, but even they don’t really know what’s going on in there. It’s what’s known as a ‘black box’. They just input the data, set it running, and see what comes out at the end. There’s no way to set absolute rules for how it behaves, because they’re not in control of the process.

Stealing Art to Fake Humanity

That capacity for producing language didn’t spring up out of nowhere, of course. OpenAI, the creator of ChatGPT, hoovered up heaps of data off the web – about 570GB of text for ChatGPT3 alone – with complete disregard for its source, who created it or owned it, or whether it was fact or fiction or just complete bullshit. We are talking about the internet here, in all its biased, sexist, racist glory. In computing, there’s a phrase ‘crap in, crap out’, and they emptied buckets of crap in there with all the quality stuff. It all went into the mix. Everything it produces now is based on that raw material, and as well as being of questionable quality, most of that would have been protected by copyright. I should point out that while ChatGPT3 was not connected to the web – it only ran on the original dataset gathered up until 2021 – ChatGPT4, Microsoft’s Bing (based on ChatGPT) and Google’s Bard are all connected to search engines. Copyright breaches aside, while they’ve all had filters applied to them to try and sieve out the worst of the worst, it’s still worth noting that your AI chatbot of choice may have learned as much from abusive porn, conspiracy theorists and racist far-right rants as they have from Wikipedia or works of literature.

They will also have been fed on science fiction stories– which would surely include the work of Isaac Asimov – where machines develop self-aware intelligence with disastrous results, and it shows in some of the conversations people have been having with these chatbots.

But that’ll all work out fine, I’m sure.

Language can mean more than words, of course, and these LLMs can be fed on symbols, images, audio and video too, and produce them in turn. It is astounding technology, capable of amazing things, and great fun to play with – some of the things I’ve seen have been hilariously weird – but it’s vital to note that it doesn’t create anything from scratch. Its success is rooted in those hundreds of millions of photos and original pieces of artwork on which all of its images are based. If ChatGPT and its like are highly advanced predictive text, then the latest image generators are the equivalent technology for making collages of existing images. We are living in an era of plagiarism on an absolutely epic scale.

Give me a few billion dollars and access to all the images on the internet and I’d be pretty amazing too.

Instead of predicting text, image generators like Stability AI’s Stable Diffusion or OpenAI’s Dall-E are ‘latent diffusion’ models. This type of model started with software that was designed to caption photographs, so it was trained to ‘recognize’ different elements of a picture – basically to represent images as text. Then the researchers decided to try and reverse it, to see if the same process could change text into an image. It worked. In a very crude way, but it worked.

A few years later, and a diffusion model is now trained on hundreds of millions of pairs of images and captions, with each pair boiled down, embedded together as a piece of code. The software learns to diffuse an image – basically to dissolve it into a speckled mush with noise in a series of steps – and then reverse those steps to recreate it, by ‘undoing’ the diffusion.

After it’s gone through these cycles enough times with enough images, it can take any piece of noise and ‘recreate’ an image from it. Give it prompts that include references to different images, and it can mix those images together, and produce variations. This is a hugely simplified explanation (let’s be frank here, that’s about my level), but this is best demonstration of it that I’ve found. And thanks to a group of artists who are suing Stable Diffusion for breach of copyright, there’s a good explanation on their website too.

Sarah Andersen, Kelly McKernan, and Karla Ortiz have taken legal action in the US, claiming that, because latent diffusion models are basing their creations on existing images, anything produced by these models is a derivative work, which means that they are breaching copyright, and because Stability AI is open about its sources, these artists were able to find out that their work was included in those datasets – without their consent.

Make no mistake about it, these people are heroes to artist communities everywhere, they are taking on the billionaires on our behalf.

And they’re not the only ones bringing a case. There are some big guns involved too. The stock photo giant, Getty Images, is also suing Stability AI for using about twelve million photos from the site for raw material – to the point where imitations of Getty Image watermarks have appeared on images created by Stable Diffusion, which is a bit of a giveaway (seriously, Google ‘Getty Image watermarks on Stable Diffusion images’ if you want a laugh). Getty’s lawyers are looking for a jury trial and damages of up to $150,000 for each infringed work. Maths is not my strong suit, but that . . . seems to add up to a lot?

There are times when this Borg-like assimilation gets very personal. Only days after the premature death of the celebrated Korean artist, Kim Jung Gi, a French games developer announced that he’d created an online tool that could mimic the artist’s style. He said it was free to use, as long as he was credited in anything created with it. This was roundly denounced in artists’ communities everywhere as a dick move, but it also seemed like a bad omen for what was to come. The tool was rubbish, by the way.

It’s no wonder artists are now referring to these things as ‘plagiarism machines’. To listen to the CEOs whose companies have created this technology, you’d think that this mass use of other people’s data is inevitable, that like progress itself, it is a faceless force of nature. OpenAI have basically said their product couldn’t do what it does now without scraping up all the data to set it up, but it seems that more and more people are objecting to that, and they’re bringing in the lawyers too.

The original justification for this massive trawling of our data from the internet was under the term of ‘fair use’, an exception to copyright when the material is used for academic research purposes. OpenAI Incorporated was a non-profit organization devoted to the advancement of artificial intelligence . . . which then created a for-profit arm called OpenAI Limited Partnership. Stability AI, the company that created Stable Diffusion, uses data gathered by LAION (an acronym for Large-scale Artificial Intelligence Open Network) a German non-profit which makes open-sourced artificial intelligence models and datasets.

Google, on the other hand, has never been shy about their ‘your data is our data’ policy, and when it comes to feeding their hungry new LLM, they’ve spelled it out in their latest privacy policy (long story short, don’t expect a whole lotta privacy if you use Google).

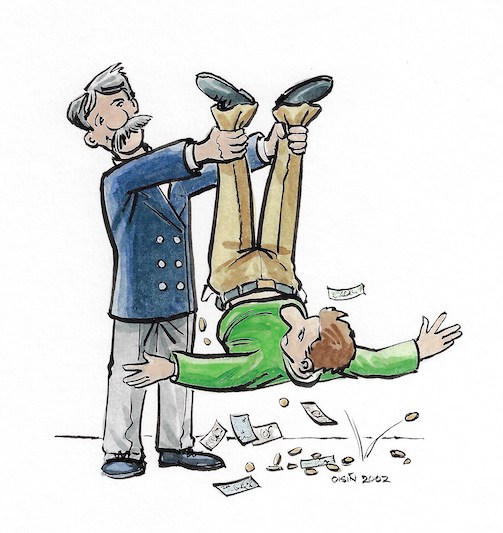

It’s weird how this technology starts off as ‘for the good of humanity’, and then quickly becomes ‘for the good of our investors’, often built on other people’s creative work. Because as all good capitalists know, creative work has genuine value – just not for the people who create it.

These are not living people with careers and families to support after all, they’re just a multitude of data sources. It’s like these guys took the wrong message from that old quote: ‘Kill one man, and you are a murderer. Kill millions of men, and you are a conqueror. Kill them all, and you are a God’. Except this time it’s art theft.

And why art? Because if you’re going to create something that seems as human, as relatable as possible, to inspire an emotional connection in your users, you look to the work of the people who have devoted their lives to exploring how to do that very thing – and create software that hoovers that work up like a super-trawler that drags all of the life out of the seas.

And in case there’s any doubt about who they’re doing this for, think about how chatbots have been used up until now, by big companies who want to replace their human staff with automatic message responses. Was it their customers who asked to speak to a bot instead of a human? Of course it bloody wasn’t. We wanted an empathic human on the end of the line. But that didn’t matter, did it?

Still, at least we can count on the companies and organizations that artists have always worked with to have our backs on this one, to resist the tide of derivative work by the moral- and thought-free products of tech bros. Those organizations whose very existence depends on artists . . . we can count on them not to encourage this, right?

Because if our creative work is subsumed by the AI tide, then the people whose business is to support that work, to curate it and distribute it, will be swamped by it next. So they’ll take a stand on this, right? . . . . . Right?

Well, not everyone, it seems.

Corrupting the Means of Production

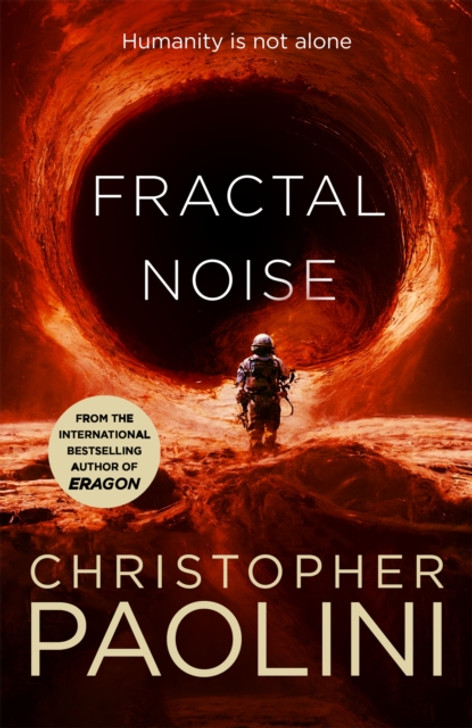

Tor is the highly respected publisher of some of the biggest names in science fiction (they’ve published one of my books too), and back in 2022, they revealed the cover of Christopher Paolini’s latest book, Fractal Noise. They used a piece of stock artwork that turned out to be reworked from an image produced by AI. They issued an apology, saying they hadn’t realized, but then went ahead with the cover anyway. Paolini is a big seller, so they could afford to spend proper money on this cover, and instead they chose a stock image provided by a diffusion model.

More recently, Bloomsbury used an AI-generated image for the cover of Sarah J Maas’s new book, House of Earth and Blood. She’s one of their top authors, and again, they could easily have afforded to pay for real artwork, but instead they went for a stock image from Adobe.

DeviantArt is an American website that features artwork, videography and photography, creating a community who can share and comment on each other’s work. With a huge store of images, it represented rich pickings for the scraping of data. Artists believed the site hadn’t done enough to prevent this from happening, and then DeviantArt announced its own version of an image generator, DreamUp, based on Stable Diffusion, and trained on images from the site, which artists had to choose to opt out of by filling out a form, to avoid having their work included in its dataset. Needless to say, this didn’t go down well with the artists, many of whom started taking their art down. While the reaction was extreme enough to persuade DeviantArt to switch to opt-in, its reputation in the art community has gone down the toilet and the site has found itself flooded with AI-generated images.

Some artists have started using a process called Glaze to stop their art from being scraped. It’s a filter, developed by the University of Chicago, that leaves the image visible to humans, but confuses an AI. If you’re an artist posting online, it’s something to consider.

Adobe, who create industry-leading tools for artists and designers like Photoshop, Illustrator and InDesign, have released their own image generator, Firefly. They’re claiming a more ethical process, as it was trained only on their own reservoir of 300 million licensed stock images, but many of the creators of those images are claiming this was not covered in the terms agreed for the rights, and it was done without their consent. It will make it far more likely that users of Firefly will not purchase stock images when they can ‘make’ their own, based on those same images.

In Britain, the Bradford Literature Festival – a festival created to celebrate the work of artists – faced a backlash because they used generative AI to create the image for their poster. Instead of paying an artist to do it.

I am so fucking tired.

Possibly the most public uproar was caused by Marvel’s new series, Secret Invasion, which used AI-generated animation for their opening titles to produce something that looks weirdly cheap and clumsy. Given that Marvel is a company that was entirely built on the work of artists, this did not go down well with fans – or artists, even those who’d produced work for the series. Marvel, and Hollywood in general, have been accused of continually driving visual effects artists to the point of burn-out as the race to produce the next CGI spectacle escalates, and this, presumably, is what they see as one of their solutions.

An AI audio-generator can now reproduce a person’s voice after recording just a three-second clip, which is already being used for phone scams. Eager to take advantage of this kind of tech, Netflix has been using their contracts to lock in the right to continue using the voices of any actors who work on their productions ‘by all technologies and processes now known or hereafter developed throughout the universe and in perpetuity’, and they’re not the only ones.

I can’t think of a better metaphor for this whole thing than using overwhelming financial power to claim ownership of someone else’s voice and then using that to make more money.

As film and television executives drool over the money-saving possibilities of AI-generated content, the Writers Guild of America is out on strike, trying to get new contract terms that reflect a world of online entertainment, streaming platforms and the relentless grind of production schedules as they’re expected to take on more and more work for less and less money. And they’re also worried that executives are going to start using Large Language Models to produce scripts that writers will then have to ‘edit’ (rewrite) for crap pay. They’re already seeing the warning signs.

Again, none of this pisstaking is essential for this tech to work. It’s interesting that the AI industry has taken different approaches to the different arts. Consider how they’ve treated text and images, compared to music. This is a paragraph from Harmonai’s website about their product, Dance Diffusion: ‘Dance Diffusion is also built on datasets composed entirely of copyright-free and voluntarily provided music and audio samples. Because diffusion models are prone to memorization and overfitting, releasing a model trained on copyrighted data could potentially result in legal issues. In honoring the intellectual property of artists while also complying to the best of their ability with the often strict copyright standards of the music industry, keeping any kind of copyrighted material out of training data was a must.’

You know why they do that for music? Because the music business is as litigious as hell and record labels may not always take proper care of their artists, but don’t you ever dare mess with their profits. Even the tech monolith that is YouTube toes the line where music copyright is concerned.

Still, at least here in Ireland, in this blessed land of literature, the home of Joyce, Stoker, O’Brien, Yeats and Wilde, where writing is such a respected art, our own government is doing everything it can to protect our creative work, right? . . . . . Right?

Hearing that laws around this might be changing in the UK, I decided to double-check, and I found this among ‘Recent significant changes to Irish Copyright law (as a result of the 2019 Copyright & Related Rights Act)’:

‘Extension of the existing copyright exceptions for Text and Data Mining copyright to promote non-commercial research that will facilitate the increased use of these important research techniques.’

What the ever-living fuck? I mean, does anyone really believe that this research is ‘non-commercial’ now? Anyone?

Grey Goo

Back in the world of publishing, even as DeviantArt’s site was being deluged with AI-generated imagery, Clarkesworld, a highly respected publisher of short-form science fiction, was forced to stop taking submissions as it was faced with a growing number of AI-generated stories. Editor-in-chief Neil Clarke said the quality of writing was generally poor, but as they still had to read enough of them to judge them, they were being overwhelmed by the quantity of them.

Back in 2015, I wrote this article for The Final Draft, the newsletter of the Irish Writers Union, about the first news of the Google Book Settlement. That was back when Google had decided they where just going to scan every book available in American libraries – without the consent of the authors or publishers – and make their text available to search online, and if you didn’t like it, well . . . tough, because they had bottomless reservoirs of cash and a legal department larger than most companies. That’s how tech companies roll; your data is their data, baby.

The Association of American Publishers and the Author’s Guild took a case in the U.S. in an attempt to control the terms of this mass digitization, and as a result of fighting tooth and nail for their rights, Google was forced to pay $125 million into a fund to set up a Books Rights Registry. Holders worldwide of U.S. copyrights could register their works with this new Book Rights Registry and receive compensation from institutional subscriptions, book sales, ad revenues and other possible revenue models, as well as a cash payment if their works had already been digitized. It wasn’t enough to stop Google in their tracks – $125 million was pocket change to them – but it was a sign that there was a limit to their power. I’m not sure how it would apply if you didn’t have recognized copyright in the US.

There was a time when I thought that publishing would face the same kind of piracy that the music and film industry has. The case in 2001 that brought down Napster, that mass pirating site for music, (largely thanks to metal band, Metallica), seemed to be a sign of things to come. But while piracy has become an issue for literature, the bigger issue is the swamp.

Text is cheap. Pretty much anyone can type text into a computer, and it’s even easier to copy and paste, and easier again to copy a file and reproduce it many times over. Bookshops will always have to choose what they put on their shelves, because shelf space is limited and they need their customers to trust their judgement, so they’ll keep coming back. Even if you’re not going to straight-out pirate text, once Amazon enabled people to self-publish online, it was possible for anyone to make a book and put it up in the same place where all the other books are. And while there have been some absolutely first-rate self-published books, without those filters of quality of publishers, distributors and book buyers, you can throw any old sludge up there and it’ll stick.

It did create opportunities that weren’t there before, and there was still a filter of sorts: if you had the ability, the enterprise, and were willing to put in the work, you could make a success of a quality book even if the publishers wouldn’t give you a chance. But you were up against minimum-effort merchants, quick-buck hustlers and outright copyright theft. If once, you were competing with a few thousand other new titles in any given market in a given year, now you were competing with tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, and more all the time. And an increasing proportion of it is dross. You are wading through a steadily growing swamp of shite to try and get noticed.

Now it’s possible to have a book written for you in minutes, to create a cover as quickly, and even internal illustrations. At the moment, most of it will be crap, but that quality is now just a technical issue. This technology has the work of hundreds of millions of authors and illustrators it can pull from, and if you use it, you’ll never know if what’s being written, or that image you’re looking at, is a rip-off of something that’s already out there. And the kind of people who will rely on generative AI for their stories and art will not, by their nature, have a keen eye for what makes good writing or good art. If they truly loved this stuff, they’d want to do it properly. Because for artists the experience is as important as the result.

You also can’t copyright something that’s generated by AI, because by law, copyright can only apply to something made by a human. This is bad news for anyone who wants to use them for their products, but not necessarily for the tech bros, because the value isn’t in the individual things this tech produces, but in its capacity to produce en masse, paid for by subscription. Erasing art’s individual value is part of the deal.

That said, the irony of seeing AI dudes try and copyright their prompts to try and protect their ‘process’, after their cavalier approach to everyone else’s copyright, is high altitude stupid on the level of the NFT market.

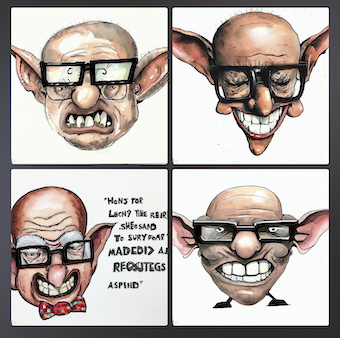

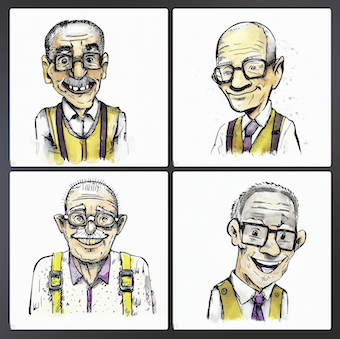

It can be easy to laugh at the stupid things Large Language Models do; like providing references to fake legal cases, claiming Elon Musk died in a car crash in 2018 or trying to convince a guy to leave his wife. We can scoff at the AI-generated images with sixteen fingers on one hand, with additional limbs or missing limbs, the confused backgrounds or the clothes and jewellery that blend like liquid into flesh. And it can be very hard to match the image in your head: The pictures here show my attempts to recreate my character, Mad Grandad on Dall-E just from prompts. Note that I included ‘friendly expression’. The first one with the sofa is the real thing.

But these are all technical issues, and they will improve over time. The amount of text these companies scraped from fan fiction sites alone is staggering – and it’s working.

In an email to The Guardian about another lawsuit, Joseph Saveri and Matthew Butterick, lawyers for the authors Mona Awad and Paul Tremblay said: ‘Books are ideal for training large language models because they tend to contain “high-quality, well-edited, long-form prose . . . It’s the gold standard of idea storage for our species.”’

Some enthusiasts of LLMs claim that they have democratized art, that it can no longer be claimed by its ‘privileged classes’ – by which they mean the people who have developed their skills the normal way. Thinking that artists represent a privileged class just because they have skills is hysterical. There have always been barriers and unfair advantages involved in achieving recognition or financial success in art, whether it’s poverty, gender, race, disability or geography . . .

But making art? One of the great things about art is that it’s cheap to get started. Writing is cheap. Pencils and paper are cheap. You can make art out of junk. There are so many ways to get into art, and if you can get online, there are dozens of cool apps that you can get for free, and no end of free advice, workshops and tutorials.

You just have to do the work. Artists like seeing the work of other artists. There are sites like Sudowrite, that claim to offer writers ‘tools’, but they’re basically for people who don’t want to write. What they’re doing is tailoring LLM functions for generating fiction. If you want to make art, then make it. Even if it’s frustrating or difficult or slow. That’s the whole point, it’s overcoming those challenges that makes it rewarding.

There’s a theory of an apocalypse known as ‘grey goo’, where self-replicating nanotechnology programmed to reproduce itself, eventually uses all the resources of the earth to endlessly make copies of itself, until all that’s left is a seething ocean of grey goo.

The quality of what a Large Language Model can produce has, at this point, ceased to be a limiting factor. It’s good enough for millions of people to start using it for a vast range of purposes. Now, we need to address the quantity.

If you’re a book publisher, one of the biggest challenges is dealing with submissions. There’s no one person whose job it is to read submissions, but read them you must, because it’s what your business is based on, and the industry is in constant need of new blood. It’s time-consuming, because out of a thousand submissions, you might only find a few worth considering, but you still have to read part of each of those thousand pieces of writing.

Think about how DeviantArt is facing a tidal wave of AI imagery. Clarkesworld was an obvious target for people trying to make some quick money, because it’s popular with the kinds of tech nerds who’d be all over ChatGPT, and it only publishes short form fiction, and LLMs aren’t yet up to writing something the length of a novel. Submissions of AI-generated text began increasing so fast that the publisher had to stop accepting them until they could come up with a system of identifying them quickly.

Children’s publishers also accept short form stories. And while the quality these LLMs can produce (for now) is easy enough to spot and rule out, it will improve, but more importantly, the people who use AI to create stories can just crank out one after another every few minutes. The submission bit itself doesn’t take very long. They could send in ten a day, twenty, thirty. Someone will have to sift through that mass, even if only to reject them.

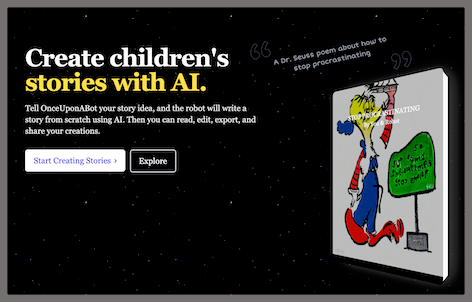

Online, there are already sites offering to help you make and ‘publish’ a children’s book using AI text and images. You can choose the style you want it written in, you can ask it to mimic a famous illustrator’s style. It’s hard to see how they’ll combine all the necessary elements with any coherence, but the vast majority of the people who use them won’t know enough to recognise that fact. A lot of them will still think they’ve struck gold, and have created the next Gruffalo, or Hungry Caterpillar or Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Writers, how many times as someone come up to you at an event and said, ‘I have an idea for a story you could write’? The people you’re pretty sure will never put in the work to write it themselves? Because now they can all do it with a few prompts.

I recently went to search for some typical fantasy character types: blacksmith, tavern owner, messenger, soldier, etc. Nearly a quarter of the images that came up were AI-generated. LLM content is going multiply so fast, it will grow to a point where it dominates the web, so the next generation of neural networks will be feeding on that content and we could get an inbreeding effect, with popular tropes spiralling into a concentrated mass, and all the inaccuracies, the biases and bigotries, the conspiracy theories and outright lies, could be condensed through repetition.

We could end up with the creative equivalent of grey goo.

The Distorted Shapes of Things to Come

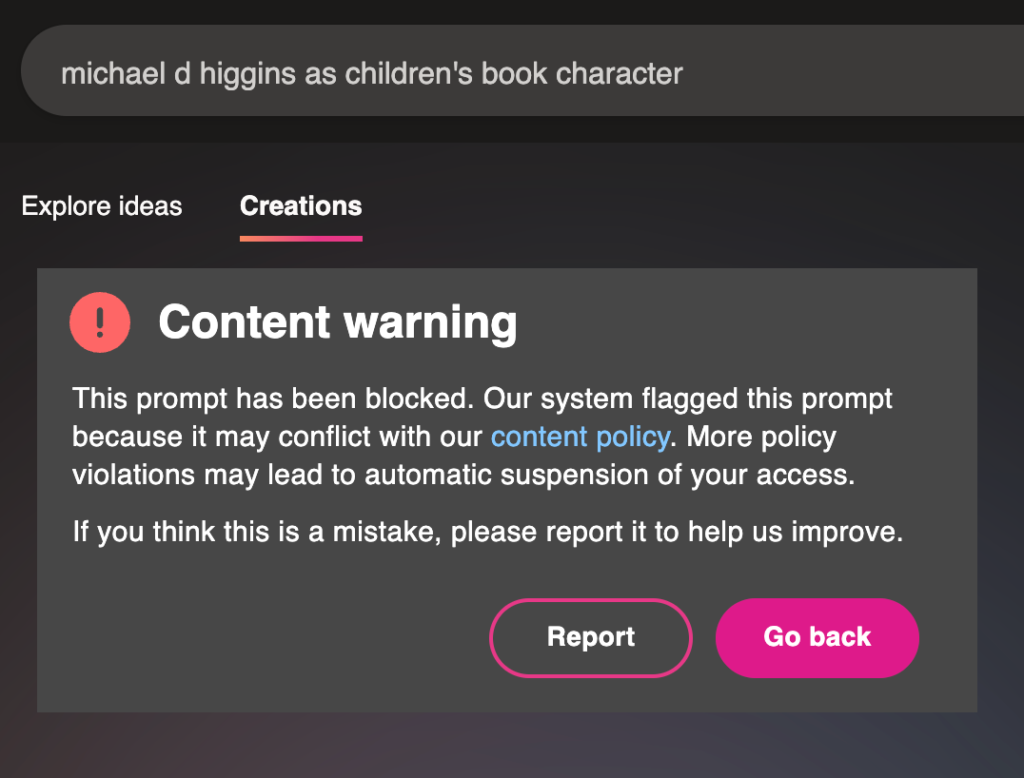

Being able to interact with people and produce in those quantities, across so many different industries, means the technology is already moving too fast for the programmers to ground it with any solid ethics or introduce effective safeguards, even when it comes to protecting their own companies – and you can tell they’re aware of that. Their success at this has been random to say the least. I couldn’t get Dall-E to represent Ireland’s President, Michael D Higgins, as a children’s book illustration (so Peter Donnelly is safe for now), but it will happily reproduce trademarked characters. Meanwhile, people are using these image generators for all sorts of inventive porn – you can bet some of it will be abusive – and they’re already being used to produce deep fakes.

It should be said that the companies have tried to train the software to filter out the worst stuff, but of course they outsourced it in true colonial fashion. As reported in Time magazine, OpenAI employed a firm in Kenya to pay people between $1.32 and $2 per hour to work through tens of thousands of clips of text, describing some of the worst stuff on the internet, in order to ‘feed an AI with labeled examples of violence, hate speech, and sexual abuse, and that tool could learn to detect those forms of toxicity in the wild.’

Then OpenAI started sending Sama, the Kenyan company, imagery for the same process, some of it illegal under US law. Sama eventually cancelled the contract.

It’s important to realize that there is no single path for this to take. Revolutionary new technology has always been disruptive, but that’s all the more reason to inform ourselves about it and adapt to, and try and influence, the new environment it’s going to create. No matter how the tech bros try to tell us that the track they’re trying to set us on is inevitable, it’s not true. It is certainly going to be a challenging time for artists, of that I’m certain – as if things weren’t tough enough already. A lot of the low-hanging fruit, the short-term, lower-paying jobs that artists take on at the start of their careers, or to fill gaps during slow periods, are going to get sucked up.

A client who might once have hired an artist for an editorial illustration, or an ad for a magazine or book cover, or for some copy for an advert or piece of design, will have to be looking at what LLMs can produce. They’ll be wondering why they should pay someone for the job, when they can get it done for a minimum subscription. That’s already coming at us, and it’s going to hit hard.

In a recent blog post, I talked about the phenomenon of celebrity children’s books, and how they were moving from being the odd tentpole project for big publishers, to standard operating procedure. I’ve never objected to them in principle, publishing is a business after all, but my argument was that if you convince people that any famous person can write a book – that the value is in that person’s brand, rather than the book itself – you risk undermining the credibility and respect it has taken the children’s book industry decades to achieve. It will confirm what many people still believe; that only books written for adults are proper books.

But now, any famous person can write a book, using AI-generated text.

So if we don’t react properly to what’s happening, all those people who think writing a children’s book is something anyone can do? They’ll be right.

Add the power of being able to mass produce art to the power of the billion-dollar attention-getting machine, the free and easy access to video content (that you don’t have to put any effort into reading), and we in the arts world are facing an existential challenge. Because what is the real value of art, when it becomes difficult to discern if it was created by a machine or a human?

Feeding prompts into a piece of software may provide you with some appealing results, but it’s not going to make you feel the way an artist feels. That’s not making art, that’s submitting an order form. At best, you’re a client. If I order a pizza delivery, I may have chosen the toppings, but I can’t claim to have made the pizza.

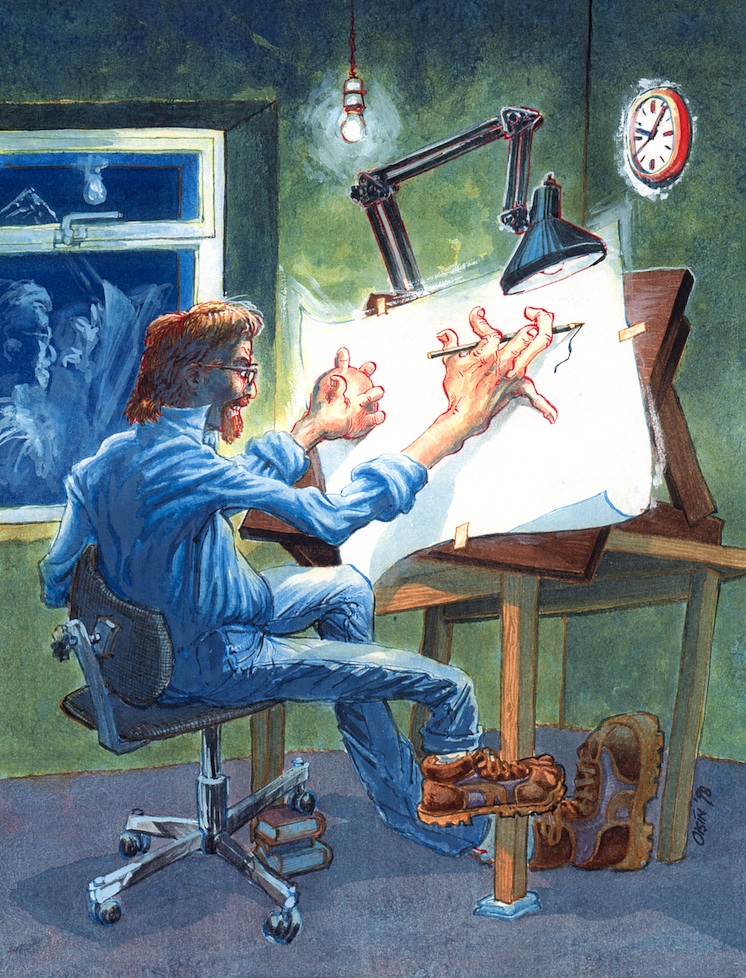

There are some who say that using images to train AI is just the same as someone studying their favourite artists, mimicking their styles and copying their techniques. I can only assume they haven’t tried this themselves, or they would know that, when you set out, there is such a gap between you and the work you set your sights on, that the struggle to get to that point changes you. It’s not just what happens at the keyboard, or at the tip of the pencil or pen or paintbrush or stylus, it’s in your mind, your emotions, in the way you use your body . . .

It’s the person you become on the way to putting the right mark on the page. And it’s that experience that enables you to reach people in ways that affect them emotionally.

We need to emphasise the importance of experiencing the making of art, not just showing an end result, especially with regard to the world our kids are growing up in.

The Enshittification Process

The tech industry does not care about individual artists – they don’t even care about being able to sell individual pieces of art. For them, it’s a numbers game, and the emotional engagement with art is just one more way to lock you into living online in spaces where they can influence what you do, what you spend, who you spend time with and how you think. As far as Large Language Models are concerned, we’re still at the early stages of what Cory Doctorow refers to as the ‘enshittification’ process. Trust me, you’ll recognize it. A simplified version of it goes like this:

1. A new online platform shows up; it’s pretty cool, offering something fresh, clever and easy to use. Users join up, and are encouraged to bring their friends. Their interactions help to make it a success. It’s the place to be, everybody wants in.

2. Once the users are locked in, relying on the service and loyal to it because all their friends are here, the platform starts using this huge user base to attract businesses. It’s no longer focussed on the users. They’re just the product, the businesses are now the customers – that’s where the money is coming from.

3. Once the businesses are locked in, the platform has a monopoly, where it’s too much hassle for everyone to leave. Now the platform starts screwing the businesses because it can.

The users are no longer getting what they used to, they’re constantly being sold to, it’s all got a bit shit, but everyone’s here, so they feel stuck. And even though the businesses are being milked to death, they have to stay where the users are. The platform can slowly turn the screws on everyone, and only has to stay just good enough to stop a mass exodus. That is enshittification.

At the moment, these Large Language Models are offering easy access to something very cool, because they need as many people using it as possible, because at some point in the not-too-distant future, one of them is going to establish a monopoly . . . and then they’ll be able to turn the screws on us. The technology will be developed to the point where we are all being used to reduce the quality of our own lives to make tech bros richer.

And whatever about Europe and the US, China is definitely paying attention.

Doing It The Hard Way

I mentioned before that TikTok, the ultra-short-format video site, has already introduced an AI chatbot onto their app that kids can access any time. And they have already perfected digital addiction. Their algorithm is formidably good at finding the next thing you’ll like. Given that TikTok is owned by a Chinese company, ByteDance, some people might be surprised that the app is banned in China. The version produced for China is called Douyin, and it has some key differences, particularly around control. Like TikTok, it has some eerily effective live filters, which make everyone look beautiful, which only help make it more addictive. If you’re under fourteen years of age, you’re limited to a certain time on the app every day, and can’t use it between the hours of 10pm and 6am. You can’t play video games on it on school days, because the government things games are bad influence on kids. For all users, there’s more emphasis on national pride, achievements in science and . . . buying stuff. There is a definite aversion to any criticism of the state.

But the government that has created a total surveillance state for their own population is happy for people outside China to spend all the time they like on TikTok which, incidentally, is being constantly criticised in Europe and America for mining people’s data. Its popularity among kids is starting to make Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and even YouTube look like an old folks’ home.

I’m trying to imagine my ten- or twelve-year-old self growing up in this world. At that age, I was starting to get serious about being a writer and illustrator. I was studying the work of the writers and artists I loved, trying to break it down and figure it out. I was a long way from where I wanted to be, and had only the vaguest notion of what it would take to get there. It was before the web, so I didn’t have those massive resources available to me, but I also didn’t have the distractions, or the insight you can get now into what these careers are really like, and how challenging they can be. I’d say that can be as discouraging as it is educational.

That kid now might already be on TikTok, challenged by the slot-machine distraction-power of billion-dollar supercomputers. He might already be using the app as a search engine, which means he’s getting a lot of his information from people who make very short videos. Even with the digital tools available online, he’s finding that learning to write and learning to draw feel torturously slow in a world that is moving at a dizzying pace. He sees witty, sharply written posts and people showing stunning new digital art every day.

As he gets older, and he struggles to get the shapes of lines right, to master form and learn about shadows and shades of colour, as he tries and fails to write the stories he can’t quite articulate, he can only see an endless, steep slope ahead of him, a very daunting climb. Meanwhile, his friends achieve incredible results by just asking a computer for what they want. It’s instant gratification, and even if he spends his whole life learning these skills, he’ll never be able to produce work the way this software can. And it’s fun to use, another distraction, so he’s not putting nearly as much time as he’d like into learning the basic skills. He gets better at achieving the results he wants with AI, better than he ever could on his own, so he doesn’t stick with doing it the hard way, because . . . what’s the point? Everyone’s using it anyway.

The more he uses it, the more the tech learns about him, tailors its responses and becomes increasingly addictive, keeping him hooked in. And now there are millions, billions who are doing the same, so even if he had wanted to make a living doing it, like all those kids who are using LLMs to do their homework (whether they’re supposed to or not) or cheat on college papers, there’s nothing to differentiate him from everyone else, because everyone can do the same thing. His attention span is short, but he also has to keep track of a much wider array of stimuli than I ever did. He never seems to have the time to develop those skills he dreamed of having.

What will it be like for young artists, growing up now? How does it feel to be a student in art college, or someone still working on their first novel or short story or poem? Will the only way they can differentiate themselves from the products of machines be to separate themselves from the online world altogether? There’s no getting around the fact that kids will already be using this technology, and that use will increase, so how do we teach them to resist its influence over them, and to use it responsibly?

Functionally, Large Language Models can achieve amazing things – if they can be developed to the point where they are reliable, which they are not, as the companies admit themselves. But just as this technology can mimic someone’s voice, it is being used by hugely wealthy tech giants to mimic emotion and human experience, so it can eventually package their empty vessels and sell them to you on subscription or use them to pitch you ads.

But we can still influence the path this tech is taking, to make the most of its benefits while limiting the damage it’s capable of doing.

Money talks. Breaches of copyright can be very difficult to establish in multiple instances and our laws just aren’t made with this kind of mass theft in mind. While the growing number of lawsuits against these companies might steer them towards a more ethical approach to getting hold of data if they get hit with grievous enough damages, the technology is already out there, and regulation with intimidating fines for breaching the law would be more effective.

GDPR in Europe gives us some potent powers, and Ireland is the home for some of the most important companies. At the time of writing, Instagram’s Threads, a new competitor for Twitter, could not be released in the EU because Ireland’s Data Protection Commission said its data harvesting didn’t comply with GDPR. The EU is also laying the groundwork for new legislation on AI, and though there’s not a lot of indication yet on how much protection it will offer to copyright, having to declare when something has been produced by AI seems to be one of the terms they’ll be including, and I think that will have be a key element as we look to the future.

If people are going to use this technology on us, the least we can expect is that we’re told what it is. This needs to be a cultural thing, as well as a legal one. People need to be aware of the effect this stuff has on us, they need strong opinions on how and when it should be used – and they need to express those opinions loud enough to influence businesses and political leaders. AI is an extraordinarily powerful tool, its impact on society is going to be enormous and there’s an argument for regulating it as strictly as we do the transport, chemical or pharmaceutical industries. Who’s responsible when it makes a mistake? When it breaches copyright? When it’s used to create or spread misinformation? None of this is clear yet, and all of it matters.

The European Writers Council have released a good statement on this, as have the Authors Guild in the US, but our laws are way behind the speed that this technology is advancing, and if we also allow the tech companies to set the pace for what is and isn’t culturally acceptable, we’ll be reduced to the role of passive subscribers.

For artists and the creative industries, this is a pivotal moment, possibly one of the most important points in our lives, and we need to acknowledge that significance. You could be an illustrator in the early stages of their career who can’t get those small one-off jobs any more, or an emerging film star who had sign away the rights to their voice. You could be a publisher or agent who can’t cope with the flood of derivative submissions, with no idea whether they’re the real deal or not, or the writer who has just seen an LLM regurgitate text that is eerily similar to one their books.

And especially for that ten-year-old kid who’s growing up in this extraordinary world; I want them to know that how art is created still matters, that it’s as vital to our lives as it ever was, and I want them to know why.

If you want to submit an order form and get a nice picture or piece of text, that’s fine. Have fun with it. It could be extremely useful too, for a lot of things, but be aware of where all that creativity came from. And if you’re looking to say something important, something that really matters to you, maybe it’s worth putting in the time to do it yourself, instead telling a machine to express it for you.

These tech giants are doing their best to turn us into a uniform mass, to steal everyone’s voices and sell them back to us. Don’t let them steal yours.