This post is for people in the children’s book industry who’ve never been to a sci-fi/fantasy convention and for regular attendees of those conventions. I think it might be of interest to both, centred as it is around the strangeness and peculiar charm, not of the attendees, but the way in which cons are organized.

And if you’ve never been to one of these conventions, you should give one a try. They’re not as off-the-wall as people think, as I’ve written about in the past, and more often than not, they’re a lot of fun. In some ways, they have a lot in common with festivals celebrating children’s and YA books.

Humour, passion, intelligence, progressive thought and stimulating discussion are all there in abundance. In terms of understanding the digital revolution, they can be an excellent place to find out what’s on the horizon and who’s doing what about it.

But there are some very striking differences between the way the sci-fi/fantasy people run an event, compared to that run by the children’s/YA crowd (or anyone else, in fact).

I read a blog post by Cheryl Morgan yesterday, about the problems of running one of these conventions – in her case, Worldcon, one of the biggest – and was surprised at the amount of aggravation and stress that seemed to be involved. I’ve come across vague controversies about Worldcon online, but have yet to hear anything specific – and to be honest, I’m not that interested. I’ve been to one Worldcon, years ago in Glasgow, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. I’ll be going to the one in London next year (also known as LonCon 3 – they have two names because there’s a different organisation behind each one), and I’m really looking forward to it.

I’ve come across vague controversies about Worldcon online, but have yet to hear anything specific – and to be honest, I’m not that interested. I’ve been to one Worldcon, years ago in Glasgow, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. I’ll be going to the one in London next year (also known as LonCon 3 – they have two names because there’s a different organisation behind each one), and I’m really looking forward to it.

I’m not a regular visitor to conventions, but I have been to quite a few. And though I’ve enjoyed all of them, I can understand how easily disputes might arise over the details of how they’re run.

I’ve been published for ten years as an author and worked for an additional ten years on top of that as an illustrator. Since my first book was published, I’ve probably done a couple of thousand individual events in hundreds of different venues, festivals, conferences, seminars and conventions in a few different countries.

So when I tell you that sci-fi cons do things a little differently to every other type of festival or conference, I’m speaking from experience. Actually, ‘sci-fi’ or ‘fantasy’ are misleading terms where these cons are concerned, as the topics that are covered can often include genres from fantasy through to historical fiction, crime to horror – a swathe of stories all wrapped up in the umbrella term ‘Genre’.

I’m not sure what ‘non-Genre’ is, though it tends to be what other people call ‘literary’ writing. Although ‘literary’ writing to me, just means a story told as well as it could be, which is not necessarily the type that wins the Booker Prize . . . anyway, let’s not get started on that.

I posted a few weeks back about the whole thing of how the creators of books are sometimes asked to do events purely for the publicity, and why it was so wrong. But then I give you . . . the science fiction or fantasy convention.

In most cases, these are set up by volunteers, passionate fans who often endure a seat-of-their-pants process as far as funding is concerned, where the audience pays a membership of the con, instead of buying tickets for talks. It’s this approach of treating the attendees as members rather than a paying audience where the big difference lies between conventions and other book festivals.  They also treat guests as a kind of higher rank of member – which includes not paying them a fee or expenses.

They also treat guests as a kind of higher rank of member – which includes not paying them a fee or expenses.

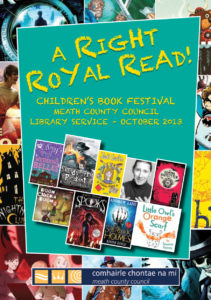

I like going to cons, but it can be a bit hard to justify. To give you an idea, here’s the kind of conversation I’d have with my wife, Maedhbh – who knows a thing or two about running events. She organizes the Children’s Book Festival for Meath every year, this year featuring nearly ninety separate events in libraries across the county.

Now, let me preface this by saying two things:

Firstly, for anyone on the con circuit who may not know it, most full-time children’s authors (and many part-time ones) do a lot of travelling around the country to promote our books, doing sessions – sessions that we are paid for. We’re expected to be able to stand up, from cold, in front of a room full of kids (or indeed, adults) and speak for anywhere from twenty minutes to an hour or more, and be entertaining, educational, knowledgeable, insightful and, eh . . . entertaining.

Secondly, Maedhbh is not what you’d call a die-hard sci-fi or fantasy fan.

So . . .

O: ‘I have to leave you on your own with the kids this weekend. I have to go to a sci-fi convention.’

M: ‘Is this for work?’

O: ‘Oh, yes. Definitely.’

M: ‘Are you getting paid for it?’

O: ‘No.’

M: ‘Are they paying any travel expenses? Covering parking fees? Are they buying you lunch?’

O: ‘Eh, no.’

M: ‘And you’ll be gone for the whole weekend? You must be getting loads of publicity out of it. Will there be a lot of media coverage?’

O: ‘No, not a whole lot. Well, somebody’ll blog about it, I’m sure. There’ll be some influential bloggers there, I’d say.’

M: ‘Is there a big audience at this thing?’

O: ‘Maybe a hundred at the whole thing, although there’ll be more than one stream of panels, so probably less than fifty at each panel. Maybe less, ‘cos some people will just hang out in the bar of the hotel. Or just talk outside in the corridor.’

M: ‘And you’re not getting paid for this? How many panels are you doing?’

O: ‘Probably two or three each day. I might try and get in on an extra one if it’s interesting.’

M: ‘And which of your books do they want you to talk about?’

O: ‘Actually, we’re not really asked much about our books. It tends to be considered bad form if you talk about your books too much on a panel. Mostly, we talk about Genre-related topics set by the organizers.’

M: ‘You’re doing three panels a day, but you’re not talking about your books? Will any of these people have met you before? Do they know your work?’

O: ‘I’m not sure. It’ll probably be most of the same people as last year, so they’ll know who I am.’

M: ‘Are these hardcore fans of yours?’

O: ‘No, they’re just people who read this kind of stuff. We have really interesting conversations.’

M: ‘Really interesting conversations? Excellent. Will you be selling your books?’

O: ‘I don’t know, they don’t always have a book stall. I can usually bring my own copies to sell.’

M: ‘So let me be clear about this. You want to leave me on my own with the kids for the weekend, so you can go and do some events where you don’t get paid, you don’t get expenses, you don’t get to talk directly about your books, you get almost no publicity or media attention, you’re speaking several times a day, but to the same audience – a small audience – and one full of people who’ve heard you speak before and have probably already decided if they’re going to try your books or not. But you get to have really interesting conversations. Have I got that right?’

O: ‘Eh . . . yeah.’

M: ‘And this is work?’

O: ‘Eh . . .’

M: ‘Unfortunately, I’ve got a work commitment on this weekend. I have to go to a Meath match on Saturday. Then I’m going to meet up with my family the next day to talk it over again. So if you want to go to this convention thing, you’ll need to find someone who can take the kids for the weekend.’

Which is why I don’t go to more conventions.

But this is not really a gripe about not getting paid to be a guest at conventions. I’ve had that rant already. Nor do I want to try and get at any one person who runs festivals. I’ve met Cheryl Morgan, and I don’t know her well, but when I hear of her and others like her – the ones who do all the work – taking a lot of grief over what someone did or didn’t like about a con, I think of our 13-year-old and his football.

He plays GAA and soccer, and the days and times of training are always changing and we hear about upcoming matches at very short notice. It’s a pain in the ass. But we can’t really complain too much about it, because these teams are run by parents who are doing it for free, for the love of it.

They’re the ones putting in all the time and effort, so it would be churlish to criticize things when we’re inconvenienced sometimes. It’s easy to stand back and make comments when someone else is doing all the work.

But it’s the membership versus audience tickets thing that I think really needs looking at – and most conventions are run along these lines.

Conventions are effectively festivals. They are run to bring people together to celebrate a certain type of book, comic, film etc. But there seems to be a determination to run them as if they’re a sports club. There’s a real amateur ethic – where it’s frowned upon by some to have paid staff working on a convention. In many cases, there is minimal sponsorship. I find this bizarre, particularly with the huge amount of work needed for bigger conventions, especially given the increasingly professional approach to running other kinds of book festivals.

And once you reach a certain scale, you’re expected to be professional whether you’re getting paid or not. Once you’re charging a hundred quid a head membership and you’re taking people’s credit card details, you need to be well organized, contactable, responsible to your audience. If I’m handing over my credit card details to you, there’s only so much slack I can cut you because you’re a volunteer. But running a professional festival is very hard to do unless someone’s manning an office somewhere with regular hours. Convention organizers have to take this responsibility on themselves, at great cost to them in time and expense. Why shouldn’t they get paid for it?

But where’s the money going to come from? These things are often run on a shoestring and I get a definite impression from con organizers that they’re constantly stressed about balancing the books.

I think that comes back to the ‘sports club’ mentality. Granted, it does make for a very warm, friendly atmosphere. Members are treated as people who are expected to get involved, help spread the word, to show loyalty – to be invested in the process. What this means a lot of the time is that there is a lot of interaction between the organizers and audience members who are already on board, and not enough time and effort put into reaching people outside of the club. You don’t get many new members in every year; you’re preaching to the converted. This approach also means that members who’ve been around a long time have opinions about how it all should be run – and expect to be obeyed – even if they don’t do any of the work. And I know I might seem to be doing just that here, but it’s not the people, it’s the whole system I wonder about.

Guest speakers, to a lesser extent, are treated with the same familiarity. If you’re running a smaller con and you don’t pay a fee or expenses (you may even ask the guests to pay membership), then the guests you have are most likely local authors who are there because they’re into it and they know the crowd, or someone who’s new and eager, but not a known name, or a more serious mid-list author whose publisher has covered their costs (which is becoming less and less likely), or who forks out their own money to visit conventions a lot, which means that your audience may well have seen them a number of times before.

If you don’t have a large enough audience, you can’t attract the big names. If you don’t even have enough mid-list names, you can’t attract the audience – or sponsors – so you don’t get in enough money to cover your costs. If it costs your speakers money to come to these things, when they get paid to attend other festivals, they’re much less likely to come to yours. It also discriminates against writers who cannot afford to travel and stay somewhere at their own coast, as well as having to cover the membership fee.

If you have the same guests every year, even your loyal members get jaded. And when you get right down to it, the success of anything like this is judged on the experience of the audience. But in ten years of being published as a writer, most of those years spent working at it full-time, I’ve seen the culture of book festivals flourish. There are many more, in Ireland at least, than there have ever been before.

If you have the same guests every year, even your loyal members get jaded. And when you get right down to it, the success of anything like this is judged on the experience of the audience. But in ten years of being published as a writer, most of those years spent working at it full-time, I’ve seen the culture of book festivals flourish. There are many more, in Ireland at least, than there have ever been before.

Even with arts budgets being slashed, these festivals are professionally run, well promoted, supported by their local communities and they can often attract big audiences, proper sponsorship and big name authors. Some can now boast a dedicated full-time staff and a permanent office. Normally, they’re in league with their local arts office or library, both of whom have the potential to source a venue for free. And if con organizers think that these people are all less passionate or motivated about their work, then they’ve never been to one of these festivals.

There is so much ability and experience among convention organizers, and they have such a passionate audience, it seems strange to me that the process is so stressful that organizers often get burned out after a few years. And yet the model for doing these conventions differently is already being used and used successfully elsewhere. Wexworlds was the first attempt to combine the eclectic quirkiness of a sci-fi con with the energy and fun of a children’s festival and I thought it worked really well, but it was run by an arts office facing budget cuts and only ran for a couple of years. I’d love to see something like that done again.

There’s huge potential in combining the experience of con organizers with the resources of libraries and arts offices, while taking a more professional approach to sponsorship, promotion and audience building. I like conventions, but I’d love to see them run more as a festival, a celebration of the work they centre round, rather than as a club for fans, some of whom clearly don’t appreciate the work the organizers have to put in and whose work sometimes seems as if it’s something to be endured, rather than enjoyed.

Great post. Sorry I don’t have time to respond in detail today.

Great post.

For Worldcon the issue is that it is a travelling convention…. but I would like to know if the “we will bring the festival to you” does change the attendance each year.

(Disclaimer – I got here through a link on twitter, and I’m not familiar with your blog. I’m just interested in conventions.)

I like festivals, but I really, really like the community of fan run conventions. The sense that you make something together, and get there all on equal terms – with no strict differences between fan and pro – to celebrate the ideas and the art of the thing we love.

You see, what I want is exactly “a club for fans”. That’s the whole point of a convention. Fandom.

Perhaps the thing is that cons don’t work as well if they get too big? The bigger event, the more people will come there and see it as a show and expect to be entertained. So it doesn’t work the way we ideally want it, it doesn’t become a community permeating the event.

I understand the problem of “working for free”, of course. Perhaps what we see now is the aches of a field that has grown out of its old clothes. Many authors have never been SF fans and don’t identify with the community. And they see it as work, and not as getting together with their tribe.

And maybe this is not the right forum to say this, I just happened to write it here. But it is another perspective, anyway.

Thanks for the comment and I understand the point. But I’ve been to a lot of different types of festivals, and there is normally a community feel in the good ones – no matter what type they may be. It’s how each one is organized and run and the personalities involved that makes the difference, not the adherence to a particular system of organization. That said, the best cons I’ve been to have been a match for any other type of festival.

The reason Worldcons have “two names” is tradition, going back the 70-plus years the event has been running. There’s no central company running Worldcon. It’s not like the traveling road show events that go from town to town. Every Worldcon is effectively a brand new, start-up convention that has to be organized from scratch with no funding other than what the members pay in, and after the convention is over, the tent isn’t just folded up, it’s burned to the ground. The legal entity that ran the 2005 Worldcon in Glasgow, for instance, was wound up after the bills were paid and a small surplus donated to future Worldcons. The legal entity running next year’s Worldcon in London is completely different from the one that ran this year’s Worldcon in San Antonio, Texas. (And indeed, the entity that ran the 2007 Worldcon in Yokohama continues to raise funds to pay for the JPY 9 million deficit they ran up; nobody else was liable for it but themselves.) Consequently, for reasons of tradition, every Worldcon is an entity to itself and traditionally gives itself a name of its own. Loncon 3 refers to it being the third London Worldcon, but it is otherwise unrelated to the past two London Worldcons.

Although I co-chaired the 2002 Worldcon in San Jose, California (“ConJose”) and am deeply aware of the traditions of Worldcon, I am growing more concerned that the tradition of every Worldcon acting totally independently, including investing most of its marketing into its own name rather than the Worldcon “brand,” is not a good thing. However, all but one or two Worldcons have done it, and even the ones that didn’t have an official name were given unofficial ones by fans that seem to have more staying power than their official ones.

I think it likely that nobody in their right mind would ever organize Worldcon from scratch the way it’s currently organized. One of the difficulties we have in explaining the event to people who haven’t attended it regularly is that its organization structure is astonishing counter-intuitive to most people. It has grown up slowly, accumulating traditions, and somehow has managed to keep going in its crazy-quilt way for over seventy years.

Very interesting comments.

Book festivals in the US are very different from in the UK, where they seem to be ubiquitous. We have the National Book Festival in Washington in September, the ABA (which is the professional book convention that brings together independent book stores, publishers and writers), and genre-related cons like Worldcon, Romance, Mystery, Horror… While a few cities have book festivals, it’s rare to see them in smaller town. The last few Worldcons have reached out more to local libraries for some cross-pollination, and I hope it’s a direction Worldcons will continue to go in.

The basic problem with Worldcon funding is every Worldcon basically starts with no money. They’re big enough to require Convention Center facilities (in most cities), and Convention Centers are increasingly expensive. They also have trouble getting sponsorships.

I worked on the Texas Worldcon, and we were constantly worried that we weren’t going to pull in enough at-the-door memberships to break even. We worked very hard to take advantage of any chance for publicity that we could find, and wound up getting many more at-the-doors than we expected. It’s great that we got this added income, it means we’ll have more money to pass along to London and Spokane. But we couldn’t rely on this money coming in.

Thanks Laurie. This seems to be a common problem with any festival, but it’s treating people who are not part of this community as ‘outsiders’ (note some of the comments here) that I don’t get. As if it’s a religion rather than a festival. Surely organizers WANT a decent audience for their event?

Turning our cons into professionally run book festivals would completely change the experience.

I get how weird it seems from the outside, when you get paid to do superficially similar events. Howver, to us, the differences are important, and professional book festivals are not what we’re about. SF cons are gatherings of friends and family-by-choice.

Terminology differs quite a bit even within fandom, but by the terms used in my neck of the fannish woods (northeastern US), it sounds like you go to these events as what we would call a program participant, not what we would call a Guest. Program participants are assumed to be members of the (fannish) community, not outsiders coming in to entertain us. Convrntions that have the cash flow to do it often comp the mrmberships of program participants, but the smaller ones often can’t, and program participants are generally assumed to be just as interested as the rest of us in having the con at least break even-to have a personal stake in there being a Next Year.

Capital G Guests–Guest of Honor, Guest Artist, Special Guest–different cons have different categories and nomenclature– usually do have their expenses covered and/or a per diem, but no “appearance fee” because, again, they are assumed to be part of the community that’s honoring them.

What we get out of it is that this IS our community–our friends, our adopted family, for many of us the subculture we grew up in. Second- and third-generation fans are not uncommon, even as we recruit new people who find us and enjoy what they’ve found

With rare exceptions, someone who had to be paid to attend wouldn’t be happy with us and we wouldn’t be happy with them, not so much because of the money per se, but because botn sides would have expectations at odds with what the other expected.

As for prifessional staff: small conventions, most locsl and rgional conventions, couldn’t afford it. Worldcon could–if Worldcon dtayed in one place and were one entity, rather than being a movable feast organized by a different group every year. Let me emphasize that: Worldcon is run by a different sponsoring group and organizing committee every single year. Yhere are people who attend and work on most Worldcons, but the people at the top, the chair, the officers, the division heads, are different every year.

There’s no practical way to have paid staff. (This annual change of organizing group is also why Worldcon has two names: Worldcon and the name that year’s committee uses.

I make no claims that this does or should make sense to those looking in from the outside. 🙂

Thanks Lis. I wasn’t suggesting that all cons should have paid staff – any more than other smaller festivals can afford them, just that it shouldn’t be treated as a negative thing and nor should striving for bigger audiences. You can always find a smaller bunch of people to hang out with at a big event.

You could have mentioned to Her Indoors that you’ll be talking to X, that guy who’s got his name on the writing credits of that very popular TV show in the bar during the con, and there’s that panel headed up by a couple of top editors on how to sell Young Adult fiction into the US market, your European agent is going to be there on the Saturday and you’ve got a chance to talk to her face-to-face and discuss future work etc.

A convention can be just for fun but for professionals writing in “genre” they really are a working weekend if they plan ahead. Several pros I know go to cons and do panels and signings and enjoy the social aspects of the event but they also schedule meetings with editors, small press publishers, prospective collaborators etc. who will also be there. I don’t know how often this happens at literary festivals and the like.

Thanks for the comment, Nojay. Yes, all of those things happen at other book festivals too – and yes, there’s plenty of socialising as well.

Fascinating perspecting, thanks for writing it up! You’ve clearly seen enough real SF conventions to have some actual understanding of them, and you know a LOT more about the other literary events than I do.

I’ve been going to SF conventions since 1972. I’ve essentially never been to any other sort of literary festival, because I don’t find the offerings the slightest bit interesting. I don’t want to hear authors promote their books primarily, and I mostly don’t want individuals pontificating on what they think they know (except in the relatively rare cases where they know so much it’s worth it). And I don’t want them all hidden away from the members except when they’re “performing”. I don’t want to relate to “celebrities”, I want to interact with fellow SF fans, some of whom write, edit, illustrate, or play other professional roles in the field, some of whom do not. (My wife and quite a lot of my friends write SF and fantasy, and at this point quite a few editors are friends as well.)

Each Worldcon chooses an individual name that (usually) reflects the location where it’s held. Loncon 3 will be the third time that a Worldcon has been held in London. Last year’s Worldcon, Chicon 7, was the seventh time that Chicago has hosted a Worldcon. And this year’s Worldcon, LoneStarCon 3, was the second time that a Worldcon has been held in Texas (San Antonio, to be specific.)

As if it’s a religion rather than a festival.

That’s almost painfully accurate. Or rather, it’s close enough to make me wince, without being entirely on point.

The traditional F/SF conventions started out as a physical outgrowth of what were essentially distributed clubs. A chance for people to meet in person.

Because people tend to define themselves in terms of both what they are and what they are not, in the 1970s and 1980s, there was a lot of resistance to the arrival of fans of (primarily SF) television and film. They were different, not “real fans”, and they were successfully kept out. At the same time, the conventions catering to media fans were commercial enterprises (I can’t recall if tiered memberships for media conventions were an original feature or added later), and, if memory serves me right, some of the media convention runners made a play at expanding into more traditional conventions at the same time.

It was this confluence that set this strong “we are not like them, we do not do professional shows, we have members not attendees” meme into the older stream of fandom. Now, I’d say that this is a distinction without a difference; there are far more volunteers at the larger events with full time staff than there are at the traditional conventions just because of their scale, and there are certainly plenty of people at “fannish conventions” for whom membership is just another word for ticket. But nonetheless, this is a real keystone of self-identity that you’re seeing now.

((If we fast forward another generation, we see two more events collide and accelerate each other. The first are the arrival of the large scale “big tent” conventions with full time staff (some non-profit, some for-profit), and a generation of fans who unknowingly recreated the events that led to literary fandom in the first place. Specifically, the fans who came of age online, on mailing lists and later web-sites and private forums for fans of particuilar shows (or games, or films, or television, or some mix of the above) and wanted to get together in person.

In some cases they integrated into existing traditional conventions, but in many cases, they were either rebuffed or completely unaware. They created their own events, or went to the large well publicized events that they knew about. After all, whatever your particular interests are in the broad spectrum of Science Fiction and Fantasy, odds are very good that there are a lot of “your people” at DragonCon. ))

TL;DR: There are a lot of historical reasons the two wings of event-running/event-attending fans have diverged so strongly, and as a side effect of this, certain characteristics (even if they are counter-productive to running events efficiently) are so core to self-identity that they are highly unlikely to change.

[As with almost anything involving Fannish history, if I misremembered something Kevin should be able to correct me]

Oison@12 above.

This (” but it’s treating people who are not part of this community as ‘outsiders’”) is one of those tricky bits about considering the social dynamics of these events. I’ve been running these events since 1990, ever since I got into SF fandom. I’ve been to some other types of event occasionally but I find them to be not to my taste. Often I can pin-point why (in particular those that are focussed almost entirely on one TV show for exampleI find too narrow, but those without a focus at all I find too shallow).

I7ve been accused a number of times lately of being exclusionary simply for saying that I put my time and money into running these events because I want to run the kind of event I want to attend and that if the only way to attract new members is to fundamentally change the focus to something I’m no interested in then I will give up rather than do that. I don’t want to be paid money and I don’t want to be paying others money. We do have a “money supply problem” but it’s because too few people are willing to give one of the two things back that matter: their thanks for doing the job (sometimes called “egoboo”, short for ego-boost) and/or their own willing volunteer efforts (not grudging, and not put forward as though their small contributions are somehow more important than the large contributions of the main organisers).

We do pay for things, but usually for people from outside the community – we pay printers to print our publications, we pay webhosting services for our web sites.

I give my time in various ways including appearing on the program. But, I’m not a published SF author (I am a published author but of an entirely different kind of material as I’m an academic) and while sometimes I make useful professional connections at SF cons, it’s entirely different to what I do at academic conferences.

The issue of paying staff is a deep and complicated one, but one I am very wary of. In my professional life I am also an unpaid volunteer in one of the many professional associations, the ACM. I’m one of many academics and professionals who give of their time for free (though major out-of-pocket expenses are covered). They do have paid staff. Unfortunately the paid staff have too much power in the organisation. For example there have been a couple of aborted attempts to look at a merger with one of the other major societies (the IEEE-CS) which I’m told (I’m too recent a recruit to the ACM to have seen these happen) were primarily scuppered by the permanent staff subtly blocking the moves because one or other of them would see significant redundancies. Once you start paying staff they have their own agenda which can easily be rather different to the needs of the community and in particualr can bring significant conflict between those putting in significant unpaid labour and those being paid.

THis has been long and rambling, but one final point on some of your original comments. I tell published authors that they should come to SF conventions only if they want to do so because they enjoy them and want to spend their free time doing it. There are more efficient ways (especially with the rise of social media on the Internet) to promote your career. So, actually I agree with your wife. These events are not “work” they are your leisure time and as such need to be balanced against your family obligations, rather than taken as work time. If you go to cons because you enjoy the company of fellow fans in an intense few days of socialising, that’s great. If not, then I don’t want to exclude you, but no you aren’t really part of the community and I’m sorry if that sounds exclusionary, but any definition of a group is going to be inclusive/exclusive by its very nature.

Oisin, no, it’s not a religion. It’s family. A great, big, extended clan. As you, say, nothing wrong with a bigger audience–except that too great a percentage of attendees who see themselves as audience rather than participants has had devastating effects on cons that grew too big for the organizing club to manage effectively and bring the new people into our subculture.

It’s not some cons, but most cons that are too small for paid staff–and as I think Laurie mentioned, each Worldcon is starting off with no money.

But the big thing is that we’re organized and run differently than book festivals because we don’t have the same goals and driving purpose as book festivals. The first sf cons were organized by fans who “met” in the letter columns of prozines and fanzines, back when it was normal to publish the full name and address of letter writers. We’ve grown, we’ve changed, but we still reflect our roots: we’re fundamentally getting together with long-distance friends to talk about the interests we have in common.

Fundamentally, we’re a hobby group, and having paid staff, even if we could afford it, really would be a change in the subculture we love. We’re not running festivals, book or otherwise, even though we have some features in common.

(And I still have occasional nightmares about a certain con that grew like topsy and became what many of the attendees regarded as a festival, and the consequences that followed.)

So, yeah, we are a little odd and confusing, especially when you’re in the position of being asked to do for free, or explaining why you’re doing for free, what you otherwise get paid for. 🙂

Oisin, others have already commented on the differences between a convention and a festival. I’ll just add one small comment. Festivals measure their success by the number of people who attend. That isn’t so for conventions.

While it’s nice that others come to be entertained the convention isn’t being held for their benefit. As a result the extent to which we will tailor the event to their needs is limited.

The success of a convention is measured by the number of people who elect to join the community as a result of attending it.

Just to note that “herself” doesn’t go to the pub to watch Meath matches! “Herself” is a real fan who actually travels to support her team.

FWIW, for the unpaid volunteers who organize science fiction conventions, event planning is their hobby. We can’t put enough emphasis on the social aspects of fan-run conventions. Many of us have found long-term friends and even spouses in this community. I’ve never known a Creation con to have evening parties in the hotels they’re held. I’ve never known them to show support to non-staff members who want to host an evening party.

In addition, while fan-run conventions in themselves may not bring program participants financial renumeration, they are an excellent place for professionals to network and meet their readers. Worldcons, in particular, give writers and artists an excellent opportunity to meet editors, agents, publishers and, to a lessor extent, filmmakers. Quite often, members who attend panels may become interested in the professionals speaking and go out and look for their work. I’ve even heard names brought up at private parties between conventions. Artists, in particular, can exhibit their work in the art show and attract the interest of editors and publishers, not to mention make some money from selling their pieces through auction. I’ve known several who have taken comissions at science fiction conventions.

For anyone interested in some aspect of this genre community, there can be plenty of benefits from attending the fan-run conventions, but those interested do need to become members and take the steps to participate. The speculative fiction genre is one of the largest and most organized special interest groups in the world, it’s a shame when related professionals can’t see how important a fan-run convention can be to boosting their careers.

I also don’t think it’s just a coincidence that many Hugo nominees are people who make the effort to meet others in the community.