When it comes to technology, I often think companies with powerful new applications can fail to see the difference between ‘Can we?’ and ‘Should we?’. As private companies develop increasingly bottomless resources for storing our most personal information, we, their customers, should constantly be asking how much of this is really necessary, and how much we are giving away by letting it happen.

Back in 2010, Geekosystem reported that Facebook were introducing facial recognition software into their network’s functions. Combined with the tagging function that can be used on photos, this software could be used to ‘recognize’ all your friends in all your photos and tag them accordingly.

Back in 2010, Geekosystem reported that Facebook were introducing facial recognition software into their network’s functions. Combined with the tagging function that can be used on photos, this software could be used to ‘recognize’ all your friends in all your photos and tag them accordingly.

I found an article in ‘ The Guardian’ a while back that confirms it’s full steam ahead for the internet giant’s new facility. And an article in ‘PC World’ explains why this is a profoundly creepy development. Facebook have long shown that they can play fast and loose with their members’ privacy. Given that private communications with your friends is a big part of the service Facebook offers, this carelessness can result in deeply personal stuff you thought was treated as confidential, ending up on view to the world.

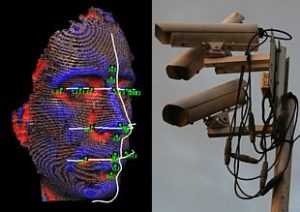

This type of software has been in use across the world in law-enforcement for some time, but Google, Apple, Sony, Microsoft and other private companies are putting it to use too.

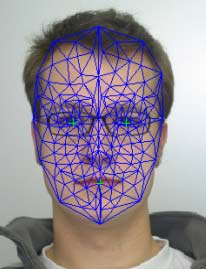

For those who’ve never come across it before, facial recognition basically works like this:

Computer software analyzes the features of your face in a photo and breaks the information down into a mathematical algorithm. It can record the proportions of your face – the relative position, size, and/or shape of the eyes, nose, cheekbones, and jaw. It then simplifies the information in the image down to the bare basics needed for identification. Another version might identify you by the blemishes in the surface of your skin; or there are even approaches that record the physical shape of your face in a 3D model. What it boils down to, though, is your face can be recorded in systems of numbers that can be identified and cross-referenced much faster than an image can – just as law enforcers worldwide can already do with fingerprints.

Except you can’t fingerprint someone as they pass you on the street.

A writer on Zippycart discusses how, in the near future, this technology could be used to target you with advertising when you’re out and about, or perhaps even get you arrested in a police state because you were once photographed in the wrong place, or with the wrong people.

Facial recognition software is already being trialled for use in schools, to replace the roll call, including one school in Dublin. I have a major problem with this – not the technological monitoring of kids’ attendance as such, but the taking and storage of children’s biometric data by a private company. I went into some of the issues around this a while back, when I learned about new systems being used to fingerprint kids in school libraries.

I have always been curious about, and interested in, new technology. But my real interest is in our relationship with its functions, and the practical ways that this affects our lives.

This introduction of facial recognition into our everyday lives is just at the early stages, and at this level, it’s still a rather fumbling, benign presence. The success rate varies, but is often much less than 50%. It can be foiled by such minor things as sunglasses, long hair, low or unconventional lighting, poor resolution and even facial expressions. If you’re on camera, give it a big smile and it might not be able to read your face.

This introduction of facial recognition into our everyday lives is just at the early stages, and at this level, it’s still a rather fumbling, benign presence. The success rate varies, but is often much less than 50%. It can be foiled by such minor things as sunglasses, long hair, low or unconventional lighting, poor resolution and even facial expressions. If you’re on camera, give it a big smile and it might not be able to read your face.

Bear in mind that if your biometric data is stolen, it’s not like a PIN number or a password – you can’t just change it. You’re stuck with the face you have, the fingertips and eyes that you were born with.

An even more sinister issue is that the developers’ biases can seep through into the programming. There have been loads of reports of people with darker skin being misidentified by these systems, because the software was only tested properly on white people.

So it’s easy for calls of caution to be dismissed as paranoia. But I figure it’s better be cautious now, rather than frustrated and powerless later. And the fact this technology doesn’t work properly yet, but is already in widespread use, is a cause for concern in itself. If it doesn’t do the job properly, why use it? Before we create massive honey-pots of information that can be lifted from a computer by anyone with the savvy to do it, misused through incompetence, or just mislaid by some eejit, let’s figure out if it’s the best way of doing things, and make sure the process doesn’t compromise our personal security.

I do harp on about this a bit, but there’s one fundamental principle I always keep in mind when I’m dealing with my information online:

Once you put something up on the web, it’s gone. Once the world has access to it, you can no longer consider it yours. And I don’t care who says what about the privacy they can guarantee online. Nobody can guarantee privacy online. Encryption can be extremely secure, but people aren’t. I always assume any online lock can be unlocked. And that’s working on the theory that the company supplying the web service to you, isn’t going to take it upon itself to do something dodgy with your information. There’s no guarantee of that either.

So when some big company tries to sell you a flash new service, but it involves using some of your most personal information – and biometric data is as personal and as important as it gets – ask not just what you could do with that technology, but what that technology could do to you.