Right then . . . the Roald Dahl thing, and Is It Ever Okay to Change a Dead Writer’s Text? I’m going to focus on the idea of the deceased writer, because living writers can change their own text if they want to, and if they don’t, they can fight their own corner.

First, let me say that I ate up Roald Dahl books when I was a kid. He is one of very few writers I would credit as driving me to become a writer. But if you think that any text for a children’s book is the pure, undiluted product of the writer’s mind, that is simply not the case. Dahl had an editor who was making changes as soon as he submitted a manuscript. He probably agreed to most of them – and if he objected, he probably got his way most of the time, certainly later in his career, because . . . well, he was Roald Dahl.

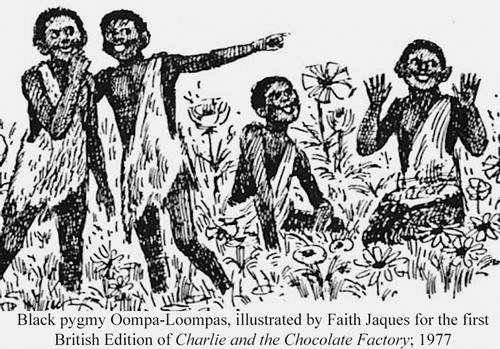

But he didn’t start off as the icon he became, and he was working within an industry that has a responsibility to kids. He even had to make changes to his books after they were published, because of proto-wokeness, when prematurely enlightened people suggested racism might be bad, and a hero who paid indentured pygmies with cocoa beans might give kids the wrong impression. But his books have been around for decades, and surely, if something has survived this long, all the dodgy kinks have been worked out?

The reaction I’ve seen online has generally called for the rights owners to keep their hands off, and as a writer who wouldn’t like his own text messed with, I’m inclined to agree. But then, I did grow up in an era when children’s books were published for kids like me – or at least an English version of me. And maybe not so much for kids who weren’t. A few years back I read all the Narnia stories to my two daughters, who were nine and eleven. I still had my original 1970s editions of them and rereading them as an adult was . . . an eye-opening experience. There were times when I had to skip bits because of the outright racism or sexism, or stop and explain why certain sections wouldn’t be considered acceptable in a book now.

And that is an important distinction to make, because when it comes to children’s books, we need to ask if something should be seen as artefact to be read in the context of its time, or if it’s to be considered a product of today’s publishing industry. And yes, that distinction matters. Some of the reactions I’ve seen to the editing of Dahl’s work have suggested that his books are too ‘edgy’, and even that this kind of meddling will have a detrimental effect on boys’ reading in particular. The issue of boys giving up reading is something I’ve been talking about since the start of my writing career, and yes, they need edgy books, but ‘edgy’ does not have to mean punching down, taking shots at those who are vulnerable or different.

And whether it’s Roald Dahl’s pygmy Oompa Loompas or Enid Blyton’s suspicious foreigners or CS Lewis’ Arab stereotypes or Susan being denied Heaven for her womanly ways, or the constant linking of Dudley Dursley’s weight with the fact that he’s written as a stupid oaf, how these characters are portrayed matters to the kids who read them – and may be compared with them. A nine-year-old will not have the perspective or context that an older reader can bring to these stories. And why should we expect them to? They’re just starting out.

It’s one thing to pick up an old book and see old-fashioned ideas, but if you print a new edition of a story with those kinds of portrayals, it means the publishing industry is giving that portrayal the stamp of approval. And don’t come at me with ‘edgy’. Terry Pratchett was able to write absurd characters with scalpel sharp humour without you ever feeling like he was punching down. Even when you laughed at some put-upon soul, he kept you on their side. I want kids to enjoy the Narnia stories, but you’re telling me you can’t take the worst of the racism out?

A book is a piece of art, but it is also a commercial product. Yes, it can be both. When I write a story, I have to get it past my agent, my publisher, and may also have to get past book marketers, booksellers, the book buyers in chains, librarians, teachers or parents before it ever reaches the kids. Any time that book is sold into another market, it may be edited again to suit the tastes and values of those new readers. Even going from the UK or Ireland to the US, changes will often be made to the text. I once had all the swear words changed in a novel because the US publisher, HarperCollins, thought they were Irish slang, (they were actually made up terms – it was set in a dystopian future) and changed them to things like ‘heck’ and ‘darn’. They also took out a gangster character’s pet tortoise for reasons I still don’t understand. They even changed the title of the book, from Small-Minded Giants to Daylight Runner. But it was a chance to get into the American market, and I gave in on some changes so I could say no to others. As for publishing in another language, writers can only guess how our text is being changed when it’s translated. And if a book sticks around long enough, it finds itself in a different market, not because of geography, but because it’s now being read by a new generation.

No children’s book is a pure example of the writer’s voice. That’s the business we’re in. It’s far from perfect, but it tends to be more thoughtful and humane than most industries, because we’re conscious of our responsibility to kids.

The later revising of published texts doesn’t just happen with children’s books. Ullyses, The Stand, Great Expectations, The Hobbit and Childhood’s End were all changed after they were published. In most of these cases it was the author’s decision, but the US edition of A Clockwork Orange was published with the last chapter removed, making for a much bleaker ending – and whether Anthony Burgess was okay with this is still up for debate. Stanley Kubrick’s film was made with the American ending. An author will often compromise on changes they don’t want so they can dig their heels in on changes they can’t bear, because a) They know they can’t judge their own book as an objective reader, b) They want their book to sell and c) They don’t want to look like an obstinate lump. So even if it’s something they’ve agreed to, it may not be what they wanted.

But now Roald Dahl is dead, so his family and publisher have to make those decisions – and his books are a moneymaking machine, one of the few in children’s publishing, and the rights holders are obviously keen to keep them current – as if they need help selling. I suspect it has as much to do with the big Netflix deal they’ve just signed as anything else. Certainly, the extra publicity this controversy has caused hasn’t hurt their sales. The books are decades old and take up space in bookshops that could go to newer writers. Are some of the changes they’re making overreactions? Yes, I have no doubt they are. I don’t know to what degree. But at the same time, I’m wary of knee-jerk reactions to changing new editions of old books.

If you believe that ideas, that stories, can have powerful effects, then you have to acknowledge that they have the power to do harm. Loving old stories does not mean that we have to tolerate outdated ideas.