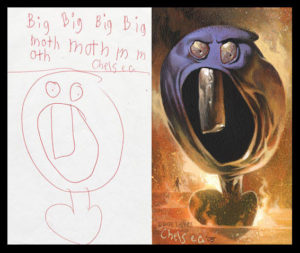

Though it’s not specifically about books for children, I wanted to mention a perfect example of how the children’s books industry hobbles itself when it comes to selling to kids. I was sent a link to a blog before Christmas, discussing a project called the Monster Engine by an illustrator in the US named Dave DeVries.  It started with his young niece drawing pictures in his sketchbook, prompting him to wonder how the pictures would look if they were painted in highly finished, realistic way. Seeing as this was what he did for a living, he decided to go ahead and try it.

It started with his young niece drawing pictures in his sketchbook, prompting him to wonder how the pictures would look if they were painted in highly finished, realistic way. Seeing as this was what he did for a living, he decided to go ahead and try it.

The idea resulted in a book, a gallery exhibition and a public demo, all based around some brilliantly spooky and funny artwork.

You can have a look at the website yourself, but I first found it through this blog where it was mentioned, and where the concept of giving children’s drawings a professional finish sparked a heated debate about whether it was appropriate to treat the products of children’s imaginations in this fashion. Some believed that this idea of rendering kids’ pictures in a highly finished way was interfering in their creative process, while others thought it was brilliant to see the wild and macabre images it produced. I fall into the second category – and it should be pointed out that DeVries didn’t just take the pictures and paint them up, he asked the kids to create monsters, and then discussed with them how he should render them.

It seems to me to be a fun thing to do, if done in cooperation with the kids, and with plenty of input from them. I see no reason to be wringing hands over it, but that’s exactly what we in the books industry do when we’re producing food for kids’ imaginations.

Now let’s take a look at a contrasting approach – that used by those who sell toys. I remember years ago, when ‘The Nightmare on Elm Street’ films were popular, I saw a toy version of Freddy Krueger’s finger-knives on sale in some shops. They were unmistakably aimed at kids – they were the size that would fit a child under ten. Given that the films were for over-18’s, who was buying these toys? Who was playing with them? The first film, at least, would have scared the bejesus out of a kid that age (I can’t really remember the others). I don’t remember any fuss over these toys.

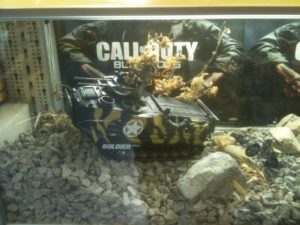

In the run-up to Christmas, I was in one of the Smyths toy stores, where I took this picture. They were using a ‘Call of Duty’ poster to promote a range of army toys (they’re not even ‘Call of Duty’ toys, they just look the part).  ‘Call of Duty’ is an 18-cert game, though some of my stepson’s mates got it from Santa last year (I love that, getting an 18-cert game from Santa). In the same shop, they had ‘Halo’ toys on display, which were very like the one shown in the photo. The latest ‘Halo’ game is rated 16+. So who’s buying these toys?

‘Call of Duty’ is an 18-cert game, though some of my stepson’s mates got it from Santa last year (I love that, getting an 18-cert game from Santa). In the same shop, they had ‘Halo’ toys on display, which were very like the one shown in the photo. The latest ‘Halo’ game is rated 16+. So who’s buying these toys?

Probably the same kind of kid that I was, when I was nine or ten. And clearly no one in Smyths toys had any compunction with using a supposedly unsuitable game to sell war toys.

My point is this: these are the same kids we’re trying to sell books to – and if you’re talking about reluctant boy readers (as we so often are), these are exactly the kids we should be trying to sell books to. Books are harder to access than games and toys – your reading has to be up to scratch. And they’re clearly not regarded as cool as games, films or even toys. For the most part, books are not objects of desire. So why are we always tripping over ourselves to protect kids from stuff that’s already in their own imaginations? And stuff that’s being sold to them by industries whose products already have massive advantages over ours? Sometimes, I think our imaginations are our own worst enemies.

On a positive note, here’s an excellent article in ‘The Guardian’ (found through ‘Irish Publishing News’), written by Faber CEO, Stephen Page. He urges publishers to be pro-active, rather than defensive, in this fast-changing environment, and talks about his excitement at all the new developments. I concur!