Ah, the things we do for love! I’ve seen a lot of different elements of this discussed on social media, but I thought it was time to write a proper breakdown of what you should expect if you decide to go full-time as a self-employed artist. This is aimed particularly at those of you in Ireland, and specifically writers, but much of what I have to say applies to most fields of art, in countries all over the world. Because many professional artists will face this choice at some point in their lives, and it’s one of the biggest decisions you might ever make.

I’m a writer and illustrator, I’ve been self-employed in those professions for most of the last thirty years, and there are so many things I wish I’d known when I started, so I’m going to lay out as much as I can here. This post ended up being longer than I’d intended, because I’m covering a lot of ground and some of that ground is lumpy, muddy or littered with obstacles. It also overlaps with other pieces I’ve written, so where they’re relevant, I’ll link to them.

If you’re already self-employed in some form, either in a different profession, or part-time as someone who sells their own art or freelances for others, a fair bit of this is going to be familiar to you, some of it might even have you putting your face in your hands, though you might find some comfort in seeing it written out. The biggest jolt will come if you’re currently employed and you’ve had enough success in your art recently to make you consider giving up the job. And that’s great if you can – I love what I do. Either way, I hope some of this is of value to you. If you’re just reading this out of interest, and have no intention of taking that leap, maybe you’ll just find it all a bit bizarre . . . and possibly entertaining.

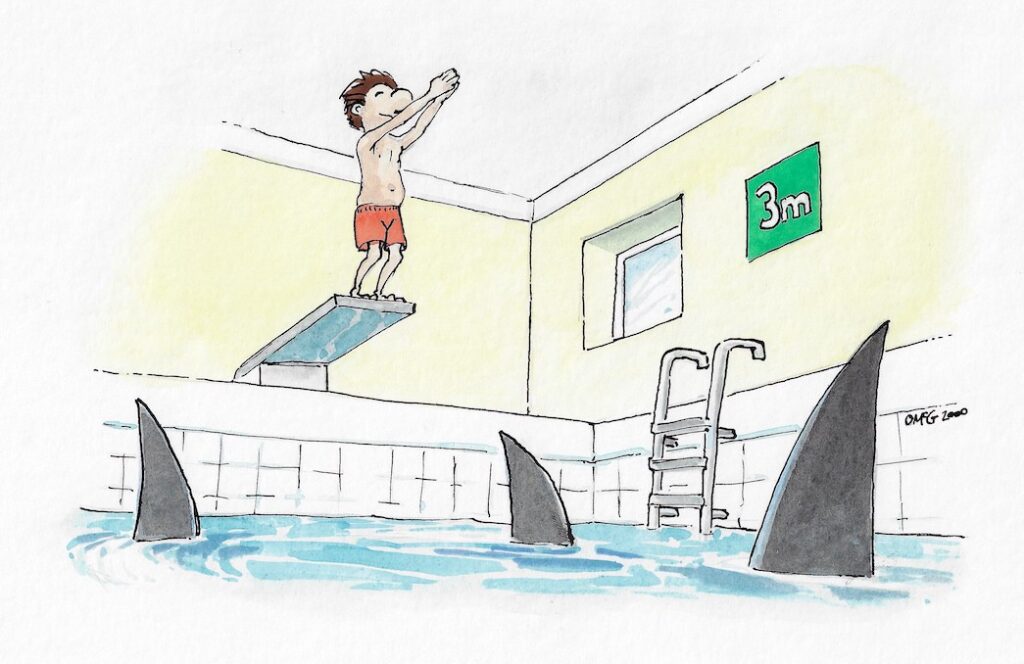

But it’s best to take that leap with your eyes wide open, so ‘let’s dive in’, as the young whippersnappers say on YouTube. (Oh God, am I getting old? I am getting old, amen’t I?)

Embrace the Oddball Social Status

One of the first things you become conscious of when you don’t have a regular income, is that society is built around the idea that everyone has a regular income, and that income stays much the same from one year to the next. Even if you’re unemployed, what little money you have coming in arrives on a regular basis. For many people, their income also increases as they get older, hopefully ahead of inflation. You can actually expect to be earning more later in life, and are very unlikely to be earning less.

But like most self-employed artists, I couldn’t tell you for certain what I’m going to earn from one month to the next, much less predict what I’ll make next year, or the year after that. Many people who’ve only ever worked in full-time employment can’t get their heads around that. In fact, it’s not just that you have to accept uncertainty in this job, you have to embrace it, even commit to it. I’ve written a whole other piece about that.

When I started out, my reasoning was pretty simple: I wanted to do this for a living. Work can take up half or more of your waking hours each day and I wanted to enjoy my day, and have as many of those enjoyable days as possible. I didn’t have much interest in artistic purity if it meant I had to find some other way of supporting myself that didn’t help the development of those skills. I figured that if I wanted to get good at this weird job, the more I did it, the better I’d get at it. Which is mostly true, but there will be inevitable compromises.

One of the interesting things about being a professional artist is that people can find it hard to put you in a box. As a career, it’s pretty classless; it doesn’t come with a particular social status. You could be a millionaire or you could be broke, but you are definitely unusual. While travelling for events, I’ve been put up in fancy hotels, and in dodgy guesthouses with grubby bathrooms and stained sheets. In general, I find that most people’s assumptions about my career are wrong, unless they work in the arts themselves.

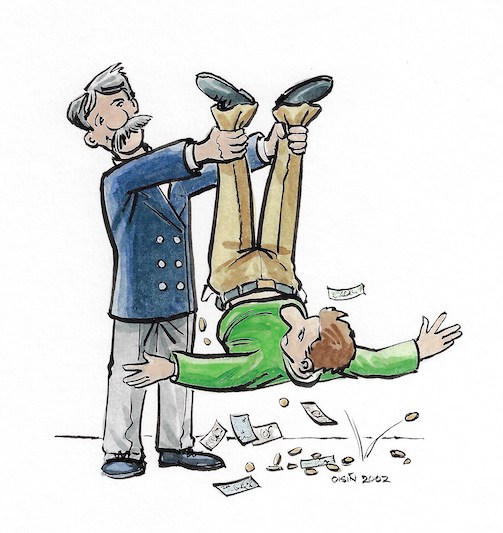

You’re Going to Have a Dysfunctional Relationship with Money

Obviously, working for yourself in a profession with no steady income and no fixed rates for the work you do, demands a lot of confidence and self-discipline. When you’re being paid on an on-and-off basis, you need to have a reserve of savings put away to be sure you can maintain regular payments over those periods when you have nothing coming in, and in a small market like Ireland, most professional artists will struggle to build up and maintain that reserve over a long-term career. How much can you put away in savings when you don’t know when you’re going to be paid next? You end up paying whatever you can, when you can. Reacting rather than planning. You’re also counting on those reserves for dealing with emergencies. You can think everything is fine and then you’re stuck with a bill for fixing your home or your car . . . or your body, or your kids need something, and those savings can disappear pretty quickly – which can happen to anyone who’s not rich, but you have no way of knowing what’s coming in to replace those losses.

Now, you might be successful enough that you always have enough reserve cash to get by, in which case some of this won’t apply to you, which is excellent . . . but it’s rare, and becomes all the more rare, the longer the timeline. As I’ve pointed out before, you could have a bestseller every year in Ireland, and never make minimum wage from your writing. Having an inconstant income will affect any chance you have of getting credit or a loan. A lot of businesses can get over a bad period by taking out a loan to cover their costs. If your credit history is a patchwork quilt with no consistency, banks don’t know what to do with you. Laugh, maybe, but not much else.

You will avoid any financial commitment you absolutely don’t have to have. A lot of the things someone in full-time employment might take for granted will become optional extras, like a car, health insurance, life assurance, a pension . . . even any hobbies or pastimes that commit you to spending money regularly. Your willingness to commit to any regular payment will often be decided by the longest dry period you’ve endured, and what you had to give up. I have as few direct debits as I can get away with, because I want to choose when I pay, rather than have that choice made for me. This ruthlessness with costs also applies to things you might need for work; renting space or equipment, subscriptions, licenses or memberships . . . and that includes having a separate phone or computer for work, so that you’re not using them when you’re not working. At some point or other, you may have to decide what you can get by with, and what will need to be sacrificed.

Getting Paid

Even artists who effectively work full-time often have more than one source of income. As part of the promotion of my books, I do events in schools, libraries and festivals. I do writing residencies of different kinds, I take on various kinds of commissioned projects, both writing and illustration, I teach courses and mentor up-and-coming writers. If you’re self-employed, you really need to make sure you’re not reliant on a single source of income, because if that’s held back or dries up altogether, you could be completely screwed.

One of the major advantages of not having any regular employment is that I’m available for these kinds of work, and the more you do, the more you’re likely to get offered. Not only do they supplement your income, allowing you to stay focussed on developing as a writer, they can create opportunities that you might not otherwise get. A number of the books I’ve published in my career came out of people knowing I was up for taking on an unusual project.

When you can’t count on your own creative projects to provide you with a secure income, being able to take these kinds of jobs on can make the difference between getting through a tough year or not. On the other hand, you can find that structured activities – where you have to turn up at a specific time or place, or meet someone else’s deadline – can very easily end up taking priority over your work, because you can always convince yourself that your own stuff can wait or you’ll find another time for it. It can be hard to strike a balance.

You get into this career to do what you love, but you can end up putting that aside to produce things for other people so you can continue making a living. This is something you have to watch out for. You have to ensure you make time for your own stuff, while you’re doing work for others. The work you do will shape the course of your career, and you need to consciously steer yourself along that course. I’ve written more on this from the point of view of illustration.

Learning how to do my accounts was a real trial and error process at the start, and although I have an accountant who does my tax returns now, I still have to do the rest myself, and I wish I’d done a basic accounts course early on, even to learn something as basic as doing up an invoice and how to charge for my time. When you’re making things up for a living, what is your time worth? Some basic tips would have saved me a lot of that time and, importantly, much of the kind of stress that comes from not being sure of what you’re doing. My admin is a lot simpler than a many other businesses, and it’s still my least favourite part of the job.

If you’re a professional artist in Ireland, you may qualify for the Artists’ Tax Exemption, which is brilliant, but it’s important to realize that you won’t be exempt as an artist, it’s only the creative work itself that qualifies. If you write fiction, and write a bit of advertising copy on the side, you can only claim it for the fiction – no matter what some think, ad copy is not fiction. For many people, the exemption has been the difference between staying in Ireland and having to go abroad for work which, of course, it was designed to prevent. Whenever I’ve had to contact people in the Revenue Commissioners with questions, they’ve always been friendly and helpful, but I find the front-line staff don’t tend to know much about exempted work.

That generous exemption is an acknowledgement that publishing and all the other industries that rely on the output of artists for their product, have been built upon the risks borne by those creators. They are challenging industries in their own right, and their foundations are the tens of thousands of careers in a state of constant change, foundations that require non-stop energy to avoid disintegration.

Thankfully, in Ireland, we are ridding ourselves, ever so slowly, of the culture of expecting artists to work for free. It used to be a regular thing when people asked you to take part in festivals and other book events, or to contribute work to a project. I rarely get these kinds of requests any more – but then I’ve been pretty vocal about this issue for a long time. There are some, however, who continue to cling on to this misconception.

It still happens that an artist will be asked to do work for free, ‘for exposure’ or for a tiny fee for the sake of some good will. Sometimes we’re asked to donate our fee for an event back to the festival or to a charity they’re supporting. Oddly, no one ever tries to suggest that plumbers, taxi drivers, doctors or other professions donate their fees to charity rather than just . . . get paid. While I might still do the odd shop event in association with a publisher, the potential royalties I can earn from sales for doing an unpaid event just aren’t worth it. Events, like any other type of work you do on the side, should be paid for. You can guarantee that everyone else involved is getting paid. I’ve written more about this too. Poetry Ireland’s rates are on the low side, but they’re a good guide to what’s acceptable, and it’s easy to refer people to them if they express surprise at your rates. I’ve also contributed to a much more detailed document on pay rates for artists in Ireland, which you can find here.

If you’re not used to chasing payments, it may come as a shock that people you work for may not tell you when they’re going to pay you, or may not pay you on time – or they may not even pay you at all.

This is unlikely to happen with a publisher – though it can happen – and I could (and may still) write a whole other post on how writers get paid in publishing, but it’s too long and complicated to go into here. I’m mostly talking about commissioned work, events and residencies.

Even a delay can be a pretty big deal when you’ve been surviving over months without much income in anticipation of a lump sum you’re due on a certain date. You might be invited to an event abroad, be told you need to fork out for your travel and accommodation in advance, and then have to chase the hosts for the money they asked you to pay to come to their event, as well as your fee, once you’ve got home. For almost everyone you work for, you can be sure that the they don’t receive their wages weeks after they’re due. It seems ironic, but I tend to find that the larger the accounts department in an organization, the more likely a self-employed artist is going to have to do more admin work to get paid.

For a single, one-hour speaking event for an arts office or a library, I might have to fill out a supplier set-up form, submit an invoice, provide a tax clearance certificate, sign a one-off contract or even actually register as an employee and be deducted emergency tax at source. Given that some of this is a new thing, and I can often get paid without any of this, it’s almost as if these departments need to make extra work to justify what they do, and apparently all our new technology is making things harder, instead of easier. You might have to apply for Garda Vetting too, the workings of which I’ve talked about here.

I’m not even going to start in on science fiction and fantasy conventions here, because I did a whole other post on that years ago.

I have an agent who handles most of my dealings with publishers, though not all, but I’ve never had an agent for illustration, and I’ve had delays in payment from all sorts of clients; individuals, commercial companies and public institutions. I’ve never had to send a solicitor’s letter, as I can be pretty persistent on my own, but again, nobody’s going to do this for you. Some business-people can behave as if art is a hobby and getting paid is a bonus, and it’s important that you burst that particular bubble as early as possible.

Putting Your Public Face On

There’s also all the extra work you do as part of this kind of life to consider, that’s unpaid or on spec. You need an online presence, and while social media is part of that, I’d always insist that you need a website as well. Social media sites like Twitter, Facebook and Instagram only show your work in a snapshot in time, concentrated on very recent work, while someone can get all the essentials of your career from a website with much less hassle. When I’m looking to find out about another business, it’s really annoying when all they’ve got is a Facebook page. A proper website is useful, not just for people who want to check out your work, but also for anyone who wants to interview or book you for an event and needs to research your background.

On that note, it’s worth putting some effort into having the basics ready to send out for any PR requests. A bibliography, a CV of some kind that gives your relevant background, biographies of different lengths (because some people may want a tweet while others want an essay) and some decent quality PR photos and copies of your book covers. Know the difference between an image that works okay on screen and something that is good enough quality to print, because they are not the same. You can find more information on that here. Publishers will often only supply authors with a low resolution copy of their own book covers. If you need a better one, ask for it.

Creating a decent site can be a lot of work up front, and nobody is going to do it for you, but it can save you a heap of time later on. Although mine has a lot of content now, it’s been built up over more than ten years, and my brother handles the technical side of it, for which I am forever in his debt. Some people put a lot of extra work into online content, including video, and while this can pay off, it can also be draining, and hugely time consuming. You have to decide for yourself if that’s worth it. Obviously, I don’t get paid to write long blogs like this one, but that’s part of the reason I only do one every now and then.

Another way you can end up putting in time on spec is applying for grants and bursaries. The application process for some of these things can seem unnecessarily complicated, and you’re more likely than not to get rejected, but if you pitch books for a living, your chances of getting an Arts Council bursary, for instance, are much, much better just for filling out a form, than they are for sending out your first book to a load of publishers and getting a book deal. And besides, if you’re a professional artist, dealing with rejection and failure is just part of the job.

Define the Shape of Your Time

Once you’re setting your own schedule, you’ll be forced to face that terrible question: How much work should you do every day? What is a normal work day? How available do you need to be? Who should you compare yourself with? It can be hard to accept that there are no right answers to these questions, especially when you’re working at home. You’ll find there’s a big difference between working long hours and being productive, and the boundaries between your personal and professional life can blur almost to the point of not existing at all.

Having the kind of structured day that’s common if you’re in a workplace with others, spares you from having to make a whole host of tiny decisions every day. It frees up part of your brain without you even being aware of it. You become conscious of how much extra thought is required once that structure is taken away, and you have to constantly plan how best to spend your time. Even when you’re working at home by yourself, you can find your time being shaped by your responsibilities to others. In a way, it’s easier to give in to, because it means less decision-making, despite how you actually need to structure it to work effectively.

Years ago, before I was married with kids, my career was also one of my main hobbies, so I worked at it on evenings and weekends. When I was a freelance commercial artist, drawing or painting anything for money, I was also letting the demands of clients set my work schedule. I was willing to do the long nights and rush things over the weekend to make some unrealistic and unnecessary deadline on a Monday morning. After I started to focus more on my writing career, I became more mercenary as an illustrator, and life got easier – and paradoxically, a bit better paid – because I wasn’t willing to waste time on jobs that didn’t pay well enough.

Once I was married with a family, my work day became shaped by my wife’s job, our children’s schedules, how much childcare we could afford and how much work I had on at any point. My wife is a librarian, and because she has to work set hours, and she has a secure income, the shape of her work day takes priority. I do still like to take some time out to do personal work when I don’t have to feel compelled to respond to others, like at evenings and weekends, because let’s face it, it’s never going to be just a job, is it? But I’m still less likely to work in my ‘spare time’ now, both because I need a life, and to avoid the kind of burn-out that can threaten the career of anyone who’s self-employed.

You also need to bear in mind how and when people can contact you. You have to set strict boundaries, or that too will end up shaping your work habits more than you want. These days, I have people contacting me in half a dozen different ways. I steer any business communication onto my email wherever possible, so it’s under control and any contact is recorded and dated. I don’t have my work email on my phone, and I don’t post it online. If you try to contact me any other way, I can’t guarantee you a reply, and I can’t promise a prompt reply to a first contact.

No one outside of my family is entitled to my immediate attention. That’s one of the advantages of running your own business.

And that’s a crucially important factor, because if you’re in a relationship and/or have children, though it might be your dream to achieve this kind of career, and you’re willing to make sacrifices for it, it’s not your partner’s dream or that of your kids. They’re just left to deal with its effects.

Your Arsehole Boss

If you’ve never worked entirely on your own, you have to be aware that it can take its toll. I like it, for the most part, I’m pretty content in my own company, though the couple of times in my life where I’ve been using my creative skills in a full-time job, in animation and then in advertising, I was struck by how different a life it was. Having the craic with like-minded people, the structured day, the buzz of bouncing ideas off each other, the practical and emotional support of having others to work with and fall back on, the security of a reliable income, the paid sick days, the paid holidays, parental leave . . . When you work on your own at home, there is none of that.

Some artists share studios with others just have to some of that social contact and to share resources, but we work in an area where there’s usually nobody to cover for you or help if you’re sick, on holiday, running late on something or can’t accept a job because you already have work on. It’s just you on your own, and you have to be happy like that, or you’re not going to be able to stick with it.

That isolation includes having to deal with every problem that might come up in a business, from unblocking the toilet to dealing with computer problems, from promoting your work to chasing payments. If you have to pay someone to help, it comes out of your income. There is no company making pension or health insurance contributions on your behalf. If you’re sick, you don’t get paid, so you’ll avoid taking sick days if at all possible. If you go on holiday, you’re paying twice, once for the holiday and once for the work time you’re missing. Because of the mindset you get into, if nobody’s there to make you take holidays, you might not even take them at all either.

One of the main problems with being your own boss, is that your boss can act like an arsehole towards you, can have unrealistic expectations and demands, and you may not even notice and probably wouldn’t quit if you did. But then, they can’t fire you either. The lack of any certainty or long-term financial security, the doubt about how much you should be working, the subjective nature of work whose worth is impossible to judge, the stress and the isolation can all have a major effect on your health, both mental and physical. I decided some time back that I had to include a walk as part of my work day, because between work and family demands, it was all too easy to put off exercising when there was other stuff to do.

You Can’t Have a Dream Career If You’re in No State to Enjoy It

It’s all too easy to burn out without seeing it coming, because your ability to judge how healthy you are is one of the things that you lose as part of burning out. Working long and inconsistent hours can mean that exhaustion becomes familiar. Lack of security can mean anxiety and tension start to feel normal. If you write or draw, that’s a lot of time sitting down, which can lead to all sorts of physical problems. I made standing-height desks for both my computer and my drawing desk about twenty years ago – I still sit at them much of the time, but I get up and down off the chair a lot – and made every effort to make my workspace fit my body, rather than the other way around, but I’m still conscious that it’s not enough.

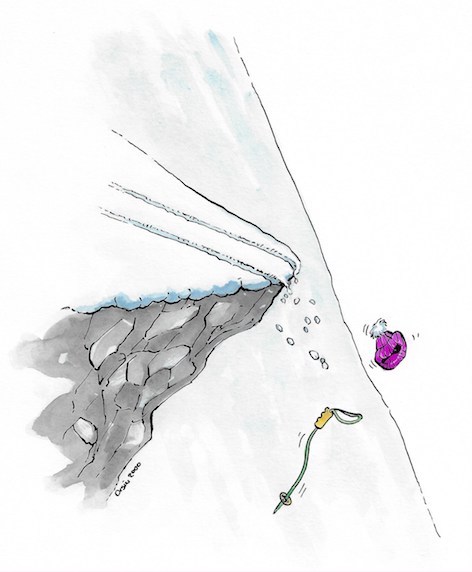

If you work for yourself in this business, you have to be aware that you are betting on your health. If you’re not working, you may be earning little or nothing, and no one can take over if you have to take a break, and there will be times when you have to choose to take a break – or change what you do – or your body or mind will make that choice for you. And it’s not a situation that improves with age.

This might involve cutting back on the work itself, or doing fewer promotional events, or changing the way you work, or the things you work on. You have to choose to be kind to yourself, to take care of yourself. On the other side of things, the insecurity of this career can lead to you avoiding risk wherever possible, always looking for the next thing from someone else, or reacting to work that’s coming in, and not taking any time to stand back and think about the direction you’re going, whether it’s what you want and what you need to be doing to get there. Taking stock like this is something I try to do on a regular basis. You get into this career because you love what you do, so it’s vital that you remind yourself of what that is from time to time, and whether you’re achieving it. And asking yourself: If you’re not doing what you love, why is that? What are you going to do about it?

It might sound counter-intuitive, but going full-time can result in you losing touch with what it is that you love about this work, because of the pressure of having to support yourself.

Reading back over all this, even I have to wonder if it’s worth it. You might well ask why anyone would take all of this on for what is often so little reward. I’ve never been a particularly defiant or rebellious type, committed to going against the flow, but I have always, always known what I wanted to do, and have been absolutely determined that I would do it – and there was nowhere that would employ me to do it, so really, the decision was made for me.

And it would be a lie to say that you fly solo to have complete control over your life. Even if you’re extremely successful, you will never be working in isolation, you’re always connected to your industry, the working environment around you. If you’re not making enough to be independently wealthy, you’re definitely not in complete control, but – and this is a crucial point – you have more control over your life than anyone else does. And I don’t need to explain to any artist how important that is when it comes to doing the work you love. The decision to take it on will make many profound demands on your life, so if you do choose to make this your full-time career, you have to make sure that you’re steering it more than it steers you.

And that means taking that leap with your eyes open, and once you land, reminding yourself as often as you can, why you took that leap in the first place.