People who take an interest in children’s books and comics learn to recognise individual illustrators by their distinct styles, but not many outside of the trade itself realise that illustrators can and do often work in more than one style.  Nor do they understand how an illustrator chooses the styles they use most often – and how those choices can affect their career. You might assume that the style they’re known for is one they chose at the beginning of their career, developed deliberately, and that they fully intended to end up where they are. If so, you’d be amazed at the random things that can influence an artist’s path.

Nor do they understand how an illustrator chooses the styles they use most often – and how those choices can affect their career. You might assume that the style they’re known for is one they chose at the beginning of their career, developed deliberately, and that they fully intended to end up where they are. If so, you’d be amazed at the random things that can influence an artist’s path.

Illustrators rarely achieve the same kind of recognition as writers in children’s books, though creative credit is far more evenly balanced in comics. If you want to become recognisable as an artist, to have a brand, it’s best to have a single distinct style that will become tied in to your professional identity.  This style will, in turn, dictate the kind of work that’s offered to you, which will affect how much money you can earn and the recognition you might receive. It can also mean that you can be in fashion as an illustrator . . . so you can also fall out of fashion.

This style will, in turn, dictate the kind of work that’s offered to you, which will affect how much money you can earn and the recognition you might receive. It can also mean that you can be in fashion as an illustrator . . . so you can also fall out of fashion.

There’s also the matter of what you want spend your time drawing or painting. The subject of your art might well be a major element in the enjoyment of the work, whether it’s caricatures, animals, machines, superheroes, architecture or whatever. Part of loving the making of art is the passion you have for your subject.

Unless you’re lucky enough to make a living from one style in your chosen subject early on in your career, however, you’re going to end up taking on a range of different jobs to get established . . . and those early jobs will have a serious influence on your development, and on the future of your career. And though I’d say technology is changing the nature of that development more than ever, art has always been influenced by the technology of the age.

Many illustrators can and do work in a variety of styles, either because they never settled on one they wanted to concentrate on, or because the opportunity to specialise never presented itself. For me, it was a bit of both.  Some who do have an established style will also feel the need to branch out from time to time, either to take on more varied kinds of jobs, or just for the sake of doing something different. We learn early on that persistence and pure chance are as important to illustrators as they are to writers.

Some who do have an established style will also feel the need to branch out from time to time, either to take on more varied kinds of jobs, or just for the sake of doing something different. We learn early on that persistence and pure chance are as important to illustrators as they are to writers.

Changing drawing styles is much more common in animation, where every artist has to work within whatever style is being used for each production. Individuality has less of a chance to express itself, because unless you’re making your own film, you’ve a specific part to play in a bigger operation. You have model sheets to stick to, to ensure a unified look to the visuals. Corporate comics companies like Marvel or DC take a similar approach; if you want to work for them, you have to conform to their style first, though you’re expected to find ways to give it your own distinct flavour.

Imagine yourself at the start of your illustration career: the biggest influences will be the artists you love, the ones whose techniques you copy over and over again, though they may be a wide and varied bunch. To pick some at random, let’s say your favourites include Norman Rockwell, Beatrix Potter, Charles M Schulz and Jim Fitzpatrick; four very different illustrators. Which aspects of their work do you choose to emulate? Perhaps you decide you want to have two or three styles you can concentrate on.

When I was starting out, nobody I knew drew on computer, though digital art was starting to find its feet. Even if you did just settle on two or three styles, the tangible materials you chose to work in would affect the look of your work. Pencil gives a different line to a brush; dip pen, felt tip or technical pen will be different again. Your hand physically moves across the paper in a different way for each of these tools; most people are more comfortable with one rather than another. Does your black and white shading style lend itself to pencil, charcoal, ink or paint?  Each one has a distinct finish. If you are providing what we used to call ‘camera-ready’ artwork for someone to scan – which was almost always the case for an illustrator, back in the day – necessity will guide your decisions. Materials like charcoal, chalk or oil pastel aren’t practical, being easily smudged or scuffed during transport or scanning.

Each one has a distinct finish. If you are providing what we used to call ‘camera-ready’ artwork for someone to scan – which was almost always the case for an illustrator, back in the day – necessity will guide your decisions. Materials like charcoal, chalk or oil pastel aren’t practical, being easily smudged or scuffed during transport or scanning.

Your choice of paint is a factor too: do you work in thin washes, as you would with water colour or ink, or do you go for thicker layers, like acrylic or heavy gouache? You normally wouldn’t use oil paints because they are too slow to dry. There’s all of this consider, even before you decide how you draw noses and eyes and all that stuff. When you do settle on a style, choosing a different material to finish it can be enough to introduce some variety.

Then there’s the time you need to think about. If the job’s not paying much, or if you’re working to tight deadlines (or both), this affects your choice of techniques.  Black and white is faster than colour, line and wash is faster than fully painted work. Simple cartoons are faster than realistic drawings. Expressionistic, gestural art can be faster than a tight, neat finish – though not always. Even small tweaks one way or the other are already influencing the style that will, through repetition and habit, become a natural technique for you.

Black and white is faster than colour, line and wash is faster than fully painted work. Simple cartoons are faster than realistic drawings. Expressionistic, gestural art can be faster than a tight, neat finish – though not always. Even small tweaks one way or the other are already influencing the style that will, through repetition and habit, become a natural technique for you.

Or maybe you’re working in Photoshop, or one of the many painting apps available these days. As styluses and slates have improved, more and more artists are drawing straight onto computer, able to switch ‘drawing tools’ at the click of an icon. In which case, your style is being influenced directly by the technology and what it can do – and also what you can afford. Most of the artists working today however, started off using physical materials and many still rely on them for some stages, despite providing the digital finished product that’s expected by publishers these days. Their drawing and painting styles will reflect this.

Even working digitally, things like detail, perspective and the need for reference images all add time, which means extra cost, which either the client has to pay for, or else you have to put in that additional time and effort at your own expense – which you might well do if it’s the type of commission you want more of.  Because it’s not just how you’re drawing or painting, what you’re creating is important to your career too. Being able to work fast does mean the ability to make more money, but only if the money’s there to be made.

Because it’s not just how you’re drawing or painting, what you’re creating is important to your career too. Being able to work fast does mean the ability to make more money, but only if the money’s there to be made.

Normally, if a job doesn’t pay much, you get it done quickly and move on to the next one. The client won’t suddenly offer to pay you more for doing nicer work. Cost will dictate other factors too; for instance, if a book’s internal pages are printed in black and white or colour . . . and all of this will affect what the illustrator has to show to a client for the next job they pitch for.

A professional illustrator’s portfolio should be made up primarily of paid work. Prospective clients don’t want to see you doing it as a hobby – you have to prove you can produce quality art to a brief and a deadline. They’ll judge you on what they see in front of them, so your past work is the single biggest factor in what future jobs you can get. The nature of paying work available to you, the opportunities you’ve been offered, start to shape what kind of artist you are.

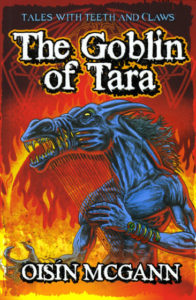

Starting out, you may want to concentrate on a style for which there isn’t much work available in Ireland or the UK, say fully painted fantasy book covers or some funky collage work.  In the meantime, you need to get established and make a living, so you take any paying work you can get, so you let the demands of the work steer your style, because you want more of the stuff that pays, so you can keep making a living. And all the time, you’re trying to work your way closer to the jobs you want to do, often by doing your own pictures on the side. Not only do you need to show other people this kind of stuff, you also need practise doing it, so you’ll be able for it when you get the chance.

In the meantime, you need to get established and make a living, so you take any paying work you can get, so you let the demands of the work steer your style, because you want more of the stuff that pays, so you can keep making a living. And all the time, you’re trying to work your way closer to the jobs you want to do, often by doing your own pictures on the side. Not only do you need to show other people this kind of stuff, you also need practise doing it, so you’ll be able for it when you get the chance.

Talk to most book illustrators, and you’ll find out they had a long and varied road to the work they do now – and chances are, they’re still taking on other types of jobs.

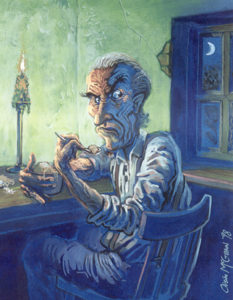

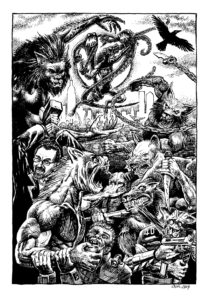

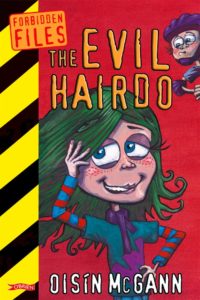

My background is more mixed up than most, which has been incredibly frustrating at times, though it’s ended up serving me well. I wanted to do that fully painted sci-fi and fantasy work. And the wacky cartoons. And the expressionistic stuff. And the Marvel-comic-style stuff.  And the . . . Actually, what I really wanted was to be able to illustrate whatever story I wrote, and in an appropriate style. For me, there were so many different kinds of career I wanted, but telling my stories took priority over getting recognition for a single style of art. The only problem was, that meant getting published as a writer as well as an illustrator. Talk about making life hard for yourself.

And the . . . Actually, what I really wanted was to be able to illustrate whatever story I wrote, and in an appropriate style. For me, there were so many different kinds of career I wanted, but telling my stories took priority over getting recognition for a single style of art. The only problem was, that meant getting published as a writer as well as an illustrator. Talk about making life hard for yourself.

For a long time, I took any job I could that paid. I did cartoons and graphic design and illustrated children’s books and school books. It didn’t pay much, so I learned to draw fast, so that I could make the time worth the money. I was a background layout designer for an animation company. I did paintings on commission on anything from paper to walls, motorbike helmets to leather jackets. Ireland was a small market and it was almost impossible to get enough work to make a living in just one style, and back then, working for clients abroad inevitably meant having to move abroad.

I don’t know if I’d have been able to keep working if I’d stayed in Ireland, but there’s no question my illustration style would have been influenced by the decision – perhaps I’d have stopped trying to make a living from varying my style, got another job and concentrated on honing one or two styles and then sought out commissions from publishers in the UK or the US.  There just wasn’t enough work to be had in Ireland back then, despite the fact that there were very few full-time commercial artists in the country. Most of the work didn’t pay well and the use of cheap stock photos was just starting to eat into our commissions. I was seeing one person after another dropping out of the trade, so eventually, like so many before me, I made the move to London.

There just wasn’t enough work to be had in Ireland back then, despite the fact that there were very few full-time commercial artists in the country. Most of the work didn’t pay well and the use of cheap stock photos was just starting to eat into our commissions. I was seeing one person after another dropping out of the trade, so eventually, like so many before me, I made the move to London.

At a meeting with a couple of people from the Association of Illustrators, I was advised to have a maximum of three styles of art in my portfolio to avoid confusing potential clients. I imagine they’d offer the same advice now – I would. I ended up spending nearly a year working night-shifts in security as I tried finding illustration work, the meagre pay supplemented with regular cartoons for a local newspaper. Any hope of a clearly defined path into London’s illustration market was undone when I got a job as an art director in a small advertising firm, where I expanded into copy writing. Having an illustrator on staff was very useful to a small company with limited in-house resources. Weirdly, we ended up illustrating a higher proportion of our ads than a company like this normally would.  Once again, I found myself responding to the demands of the jobs, rather than my own tastes, working in whatever style and whatever medium got the message across.

Once again, I found myself responding to the demands of the jobs, rather than my own tastes, working in whatever style and whatever medium got the message across.

The key point here is that, not only was I not working in a specific style, but the subject matter of each illustration was out of my control. Commercial artists don’t get to choose what they create. I had to draw everything from engineering parts to Santa Claus for corporate Christmas cards; cartoon gags about computer telephony to the Photoshopping of product photos. It was enjoyable, and sharpened my skills further, but – ironically, considering the nature of the business – I was no further along the road in terms of developing a ‘brand’.

For me, this wasn’t such a bad thing, because the books were always going to come first anyway, but as I’ve already said, look into the past of any illustrator, and you’ll probably find stories like this.  I came back to Ireland and found that publishing was changing. Illustration was being taken more seriously, and the technology meant there were more opportunities to work for clients abroad, while staying at home.

I came back to Ireland and found that publishing was changing. Illustration was being taken more seriously, and the technology meant there were more opportunities to work for clients abroad, while staying at home.

As the nature of the business has changed, the opportunities, but also the demands, on illustrators have been changing too. Illustration and design was going digital even as I was starting to learn my trade in the nineties. Physical artwork is in decline; working on paper has its advantages, and its pleasures, but it’s slower, because it needs drying time and scanning, steps we can now cut out of the process. I still love working with traditional materials, but they’re harder to fix and change, either for yourself or at the request of the client. The range of tools and effects available in art apps now is extraordinary, though the fundamental drawing and painting skills still apply. It will be interesting to see what happens as the influence of those physical materials fades and younger artists form new kinds of habits from scratch, some of whom might never get their hands dirty on charcoal or paint.  We can already see new habits forming based on effects, short-cuts and trendy techniques that didn’t exist ten or fifteen years ago – just as my generation would have developed ours. And are still developing ours.

We can already see new habits forming based on effects, short-cuts and trendy techniques that didn’t exist ten or fifteen years ago – just as my generation would have developed ours. And are still developing ours.

So next time you find yourself admiring an illustrator’s work, maybe go and have a look at their website or wherever you might find their gallery or portfolio, and see what else they have there. You could be surprised by what other kinds of things they do. And you might wonder what random happenings helped bring them to this point in their career, and where they might still want to go from there. There’s always a lot more than what you see on the page.